© 2024 ALLCITY Network Inc.

All rights reserved.

The Air Force Falcon offense is unlike any seen by the Buffs since 2013, but that doesn’t mean it’s unfamiliar to football fans in Boulder.

Take a look at this iconic play in Colorado Buffaloes history:

Darian Hagan pitching to J.J. Flanigan 30 yards downfield in a win over Nebraska en route to a national championship appearance is a seminal Buffs moment.

But it almost didn’t happen.

When Bill McCartney took over the Buffs in 1985, his teams got off to a slow start. After winning just five games in his first three seasons as head coach, McCartney was lucky to keep his job and decided he needed to make a change.

That’s when he implemented the triple-option offense and then, three years later, won a national championship.

The McCartney triple-option is different than what Air Force will run on Saturday at Folsom. McCartney used hybrid formations that combined components of the Wishbone and I formations. Colorado used 48 unique formations in the 1990 season, when you include different pre-snap motions and count both the right-side heavy and left-side heavy versions of each formation.

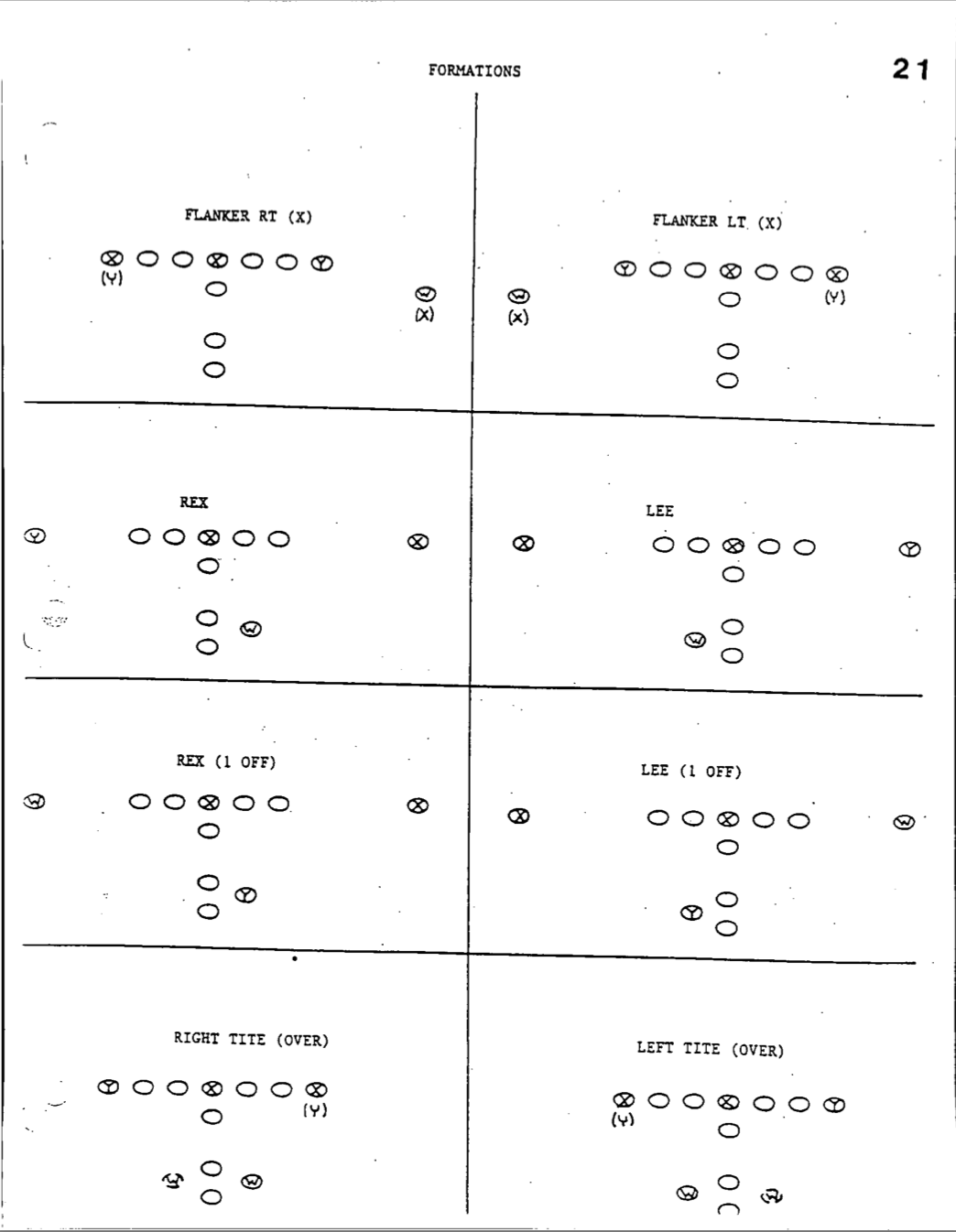

Take a look at this page of the 1990 Colorado playbook that displays eight different formations, and notice the many running backs aligned tight behind the quarterback:

These formations are typical of the McCartney scheme. Most formations featured about three running backs aligned close together behind the quarterback.

What Air Force does is different.

The Falcons offense, though based on the same triple-option concepts, is run out of the Flexbone formation. In Week 1 against Colgate, and FCS squad, Air Force used their base Flexbone formation in at least half of its offensive snaps.

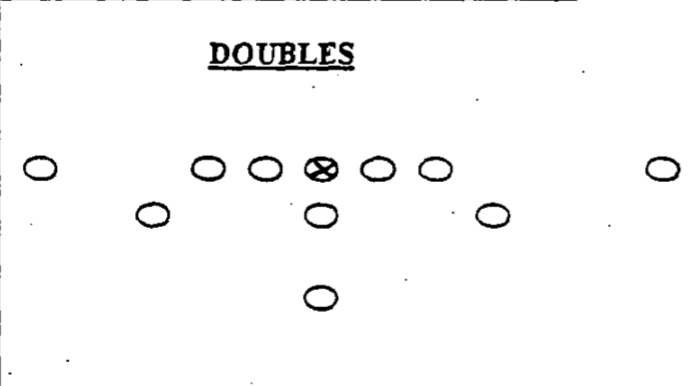

Here’s what the base Doubles Flexbone looks like, pulled from a past Air Force playbook:

Like the Colorado teams of the 80s and 90s, Air Force typically uses three running backs, they line up differently. A fullback lines up 4-5 yards behind the quarterback and two slotbacks line up in an H-back spot, about 2-3 yards behind where a tight end would normally line up on the line of scrimmage.

Here’s the bread-and-butter play for Air Force and other teams that use a Flexbone triple-option offense. It’s called Inside Veer.

The quarterback has three options on the play: First, he can hand the ball off to the fullback, who is charging straight ahead. Second, he can pitch the ball outside to the slotback, who tries to run up the sideline. Third, he can keep himself and cut up off the edge of his tackle.

The goal is to do exactly what happened above. Ideally, the quarterback gives the ball off to the fullback who gains enough yards to keep the offense “on schedule.” That means gaining three or four yards, so the offense is on pace to pick up the first down before they have to punt.

But who gets the ball depends on the two defensive players who are left intentionally unblocked. These are called the “give key” and the “pitch key.” Against the Buffs’ 3-4 defense, the give key will be the defensive end and the pitch key will be an outside linebacker.

The two unblocked players will take themselves out of the play by defending a player who won’t receive the ball, as long as the quarterback makes the correct decisions, based on his keys. That’s two fewer blocking assignments that could potentially be blown and ruin the play. The beauty of the triple-option is that it gives the offense a numbers advantage.

Take a look at another play from Air Force’s Week 1 matchup with Colgate. This time the ball goes to the slotback.

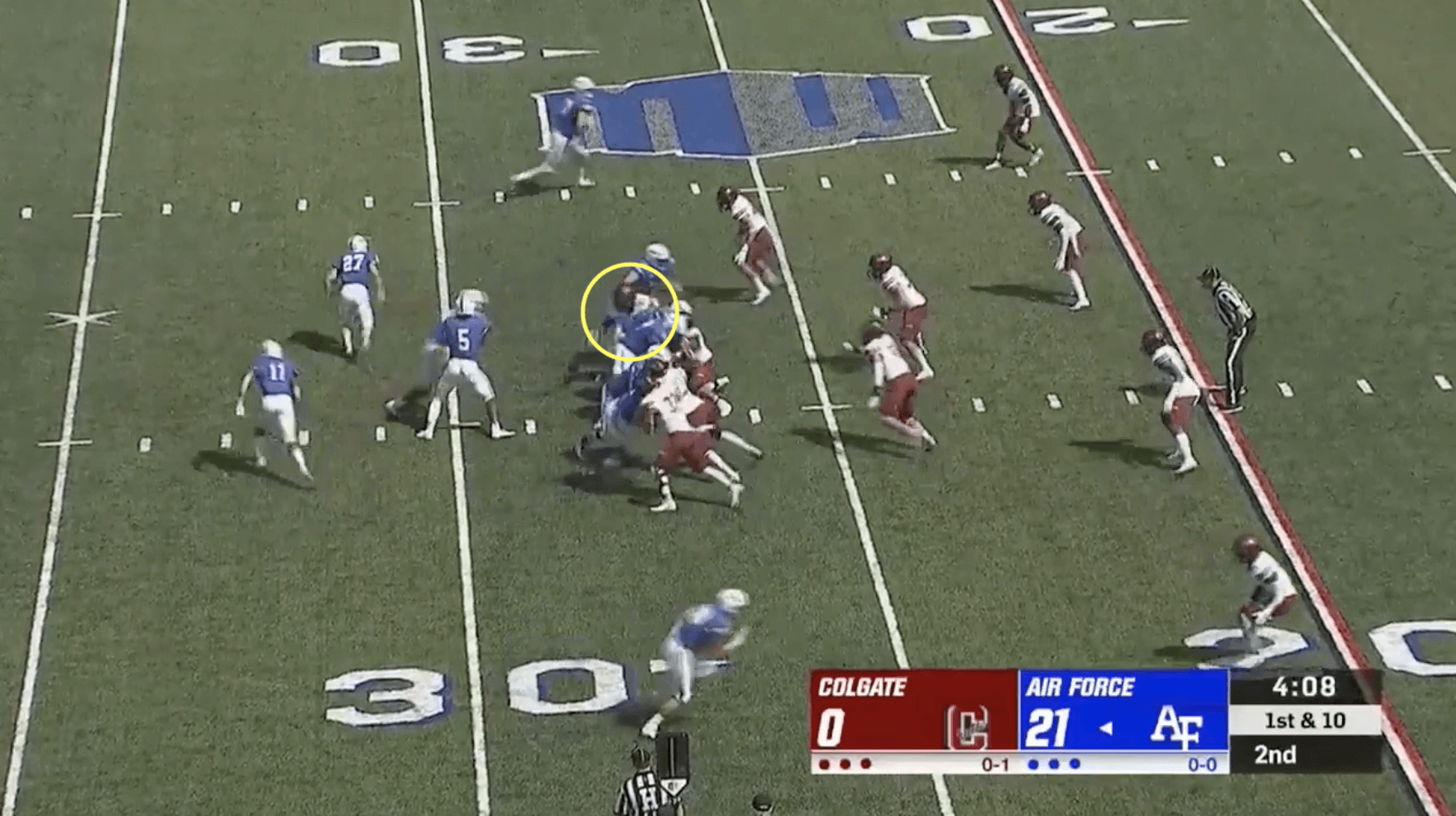

Here’s a screenshot from early in the play. I circled the defensive lineman who was designated as the give key and therefore left unblocked. Since he turned his shoulders inside to tackle the fullback instead of opening them to pursue the quarterback, the quarterback kept the ball and extended the play outside.

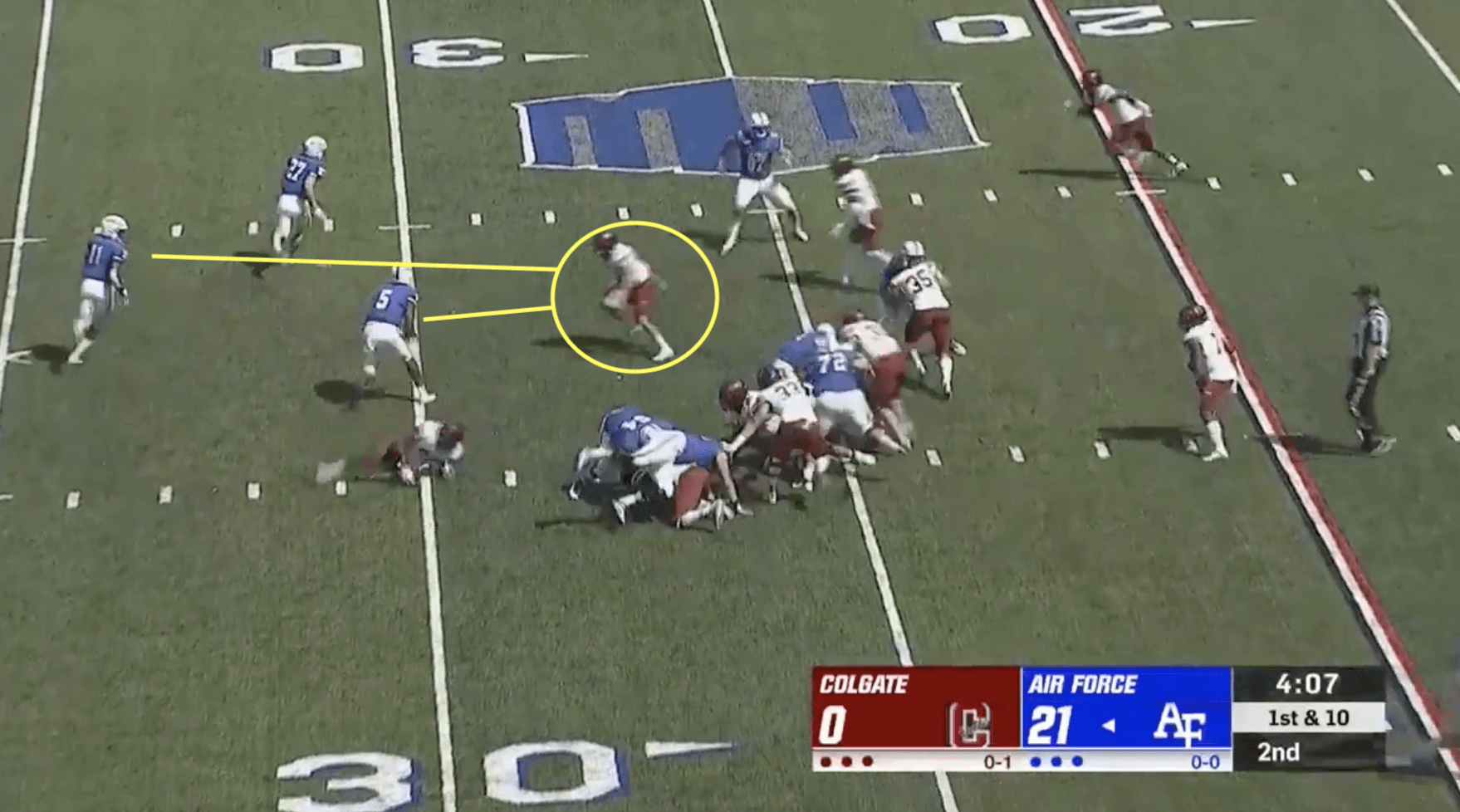

Next up is the pitch key, the outside linebacker left unblocked. Since he crashes toward the quarterback instead of keeping his width and playing the slotback, the quarterback pitches the ball to the slotback. Here’s a screenshot.

Now watch the quarterback make the reads in realtime.

Now watch the quarterback make the reads in realtime.

Alright, so that’s the basic triple-option offense out of the Flexbone. We’ll be seeing this exact play over and over again on Saturday. Where the offense gets interesting is if the defense cheats.

In the next clip, a safety (highlighted) cheats outside and gives the quarterback a running lane.

(Also note the cut blocks. Air Force typically just asks its offensive linemen to dive at its opponents’ knees to take them down.)

While it’s easy to blame the safety for blowing his chance to tackle the quarterback, the real lack of discipline came from the Colgate coaching staff.

On the previous play, the fullback pounded Colgate up the middle, just like he had all day. At that point, Air Force’s fullbacks were averaging five yards per carry just by running straight up the middle. When Colgate tried to stop the bleeding by putting more players in the middle of the field, Air Force pulled the chair out from under them.

Instead of serving as a ball-carrying threat up the middle like in the traditional Inside Veer, the fullback ran outside of the offensive line and served as a lead blocker for the quarterback. Air Force had an obvious numbers advantage outside because of Colgate’s overcommitment to stopping the run up the middle, despite no threat from the fullback, and it turned into an easy touchdown.

Watch the play again, and note that all of the backs move outside the formation and there just aren’t enough defenders outside to have a chance.

This is triple-option football.

The coaches on the Air Force sideline and in the press box are looking for every little overcommitment, whether from the opposing players or coaches. Then they think up a way to exploit it.

Here’s another staple of the flexbone triple-option, called Rocket Toss. This is a designed toss to the slotback. The twist is that the quarterback opens his shoulders away from the play as the ball is snapped, in an effort to freeze the defense. It looks like a fullback dive. Then, the quarterback pitches to Kadin Remsburg. Remsburg scored on Rocket Toss twice in Week 1. Remsburg is a beast when used as the ball-carrier in Rocket Toss, primarily because of his 4.3 speed. The split-second advantage is enough for him to get to the edge.

You’ll notice that before almost every play, one of the slotbacks goes in motion showing the defense which way the offense will run the play. Of course, Air Force coaches are just waiting for the defense to overcommit to that side of the field.

Against Colgate, Air Force didn’t have to go too deep into its bag of tricks to pull out a win, so here’s an example of how the Falcons beat New Mexico when it overcommitted toward the motion.

Air Force ran the same Inside Veer look, but instead of lead-blocking outside, the playside slotback cut inside and followed the fullback through a gaping hole. Who would’ve guessed the Falcons would run a second back through the hole out of a flexbone formation?

It’s those sorts of twists that pick up the massive gains for a triple-option offense.

Here’s another creative way to use the defense’s momentum against it. In this clip from the Wyoming game last season, Air Force runs its base Inside Veer motion, but all of a sudden the quarterback stops and runs back the other way. It’s a designed play that’s basically a flashy quarterback counter.

Beautiful.

You might notice that we haven’t talked much about the passing game. That’s because the Falcons only use it as a counter to their base triple-option looks. Against Colgate, the Falcons only threw the ball once.

![]() The pass went for 41 yards.

The pass went for 41 yards.

It wasn’t a typical Air Force pass though, so we’re going to skip over it and show a clip from last season against Army. When Air Force passes, it passes because somebody on the defense hasn’t been paying attention to their coverage assignment because he’s so focused on stopping the run.

The wide receiver runs butt-naked.

Here’s another wrinkle from the Army game. Air Force fakes fullback dive. When Navy realizes it’s a fake they prepare to guard the edge since that’s where the quarterback typically carries the ball in the option offense after faking to the fullback.

But the quarterback follows the fullback through the hole and it’s wide-open.

(Also note the use of the I-formation, which is fairly rare.)

Alright, now you’re ready to watch Air Force play the Buffs on Saturday and not miss out on how special what you’re watching can be.

The triple-option requires incredibly artful play-calling to be successful. It’s all about laying traps that the defense will fall for. Saturday will be a real test of Colorado’s discipline. Will the Buffs accept the body blows that come with defending the triple option or will they be impatient and try to strike, risking getting caught off-guard by Air Force.

“If you want to deliver some punches, you’ve gotta be willing to take some too,” Buffs head coach Mel Tucker said in his media conference on Tuesday.

Colorado can force Air Force to run inside with its fullback on every play, if the Buffs stay disciplined. It’s frustrating and boring, but it gives the defense plenty of opportunities to stop the offense from moving the chains as they slowly trudge downfield.

But if the Buffs cheat on their assignments, they become susceptible to giving up big-gainers. That’s how Air Force beats you. That’s why staying disciplined on every play is so important.

It’s easy to see the slotback go in motion and take a step toward where they play is likely going. You’d be correct 90 percent of the time. But if the Air Force coaching staff notices a trend, their master play-callers will take advantage.

If defensive coordinator Tyson Summers gets frustrated after a few six-yard fullback dives and squeezes his defense toward the middle just slightly, Air Force will attack the edges and could find a crease.

Colorado needs to focus on every single snap.

Okay. We’ve hammered that point home enough.

Now, before we go our separate ways, let’s take one last look at Darian Hagan and J.J. Flannigan running the Inside Veer out of a Flexbone-style formation in 1989.

That’s just football at its peak.

Comments

Share your thoughts

Join the conversation