© 2025 ALLCITY Network Inc.

All rights reserved.

WESTMINSTER, Colo. – It’s 10:20 p.m. on Tuesday, Sept. 11, and I think I’m about to see my first dead body ever.

A call comes in from dispatch. There’s a female, older, unresponsive, possible liver failure.

“There’s your first DOA probably,” Westminster Police Department officer No. 63, tells me as we start driving to the scene.

But a few minutes upon arrival at the apartment complex where the woman lives, there is good news: She’s still breathing, and EMTs got to her just in time to treat and transport her to a hospital. The officer, Jeff Sirkka, relays the news back to dispatch, thanks the EMTs and, within a few more minutes, is back in the souped-up SUV where I am his ride-along companion for his 4 p.m. to 2 a.m. shift.

“That’s pretty rare. She’s lucky. When you hear what was described about her, it’s almost always DOA,” Sirkka says. “But there was some adrenaline there for you, right? There was for me too. That’s the answer I always give when people ask me what being a police officer and a hockey player might have in common. It’s the adrenaline.”

If the name Jeff Sirkka rings a bell to you, local longtime hockey fan, it’s because at one time he was a paid professional hockey player in this Dusty Old Cowtown. For one glorious season, 1994-95, Sirkka played defense for the Denver Grizzlies of the old International Hockey League. The Grizz, as they were known, were a one-year phenomenon that absolutely helped make pro hockey relevant again here and helped convince the one-time owners of the Colorado Avalanche that things would work in Denver when they were thinking of buying and moving the Quebec Nordiques.

Playing at the old McNichols Arena to often sold-out crowds, the Grizzlies went 57-18-6 in the regular season, then stormed through the playoffs to win the Turner Cup championship. The team had it all – big scorers in guys such as Kip Miller, Chris Taylor, Chris Marinucci and Jeff “Mad Dog” Madill, a top goalie in Tommy Salo, two heavyweight enforcers in Mike MacWilliam and Jason Simon, great special teams and a solid, veteran defense led by Doug Crossman, Gord Dineen and Normand Rochefort. Because the NHL was locked out for the first half of the 1994-95 season, some guys who should have been playing in the NHL, guys like Zigmund Palffy, also spent time with the Grizz.

Sirkka played 58 games for the Grizzlies, posting four goals, 18 assists and 86 penalty minutes. The Grizzlies were one of 15 professional teams for which Sirkka played. They were just another stop in a vagabond career that took him from one coast (Maine) to another (Long Beach, Calif.) and many cities in between.

“I would have liked to have played a little more,” Sirkka says of his year in Denver. “But we had such a great team. It was a tough lineup to get into.”

But Colorado made quite an impression on the kid from Sudbury, Ontario. As a Grizzlies player, he met the woman he would eventually marry and have a daughter, who is now 19. He returned as a player for the Colorado Gold Kings of the West Coast Hockey League, from 1998-2001. When his pro career finally ended the next year, with Cincinnati of the ECHL, Sirkka wasn’t quite sure what he’d do.

It was, he admits, one of the toughest times he’s ever had, adjusting to the real world after a life of being paid to play the game he loved. Though he came back to Colorado, there was depression, a divorce, and just a whole lot of uncertainty. He filled his days working an unfulfilling construction job. A job in hockey didn’t seem in the offing. Sirkka felt lost in the world.

“I really didn’t know what to do anymore,” he said.

***

One day, a family friend mentioned that his cousin, Joey, was a Denver police officer. “Why don’t you go along with Joey on a ride-along,” the friend said.

“So I did. And we got in a pursuit that night, and you talk about adrenaline! It was right there where I thought, ‘Yeah, I could do this. I’d like to do this,'” Sirkka said.

Joey explained the best way to go about applying for a career in law enforcement, and Sirkka soon was at Arapahoe Community College, taking four months of police academy classes. Once he passed, he became state certified, and that allowed him to formally apply to police districts in the state. He wanted to work for the Denver PD at first, but his Canadian citizenship was a red-tape stumbling block. It wasn’t for the Sheridan PD, though, and in 2002 Sirkka was hired as an officer in the city.

In 2005, he took a position with the Westminster PD, where he remains today. Even though Westminster has the highest number of officer-involved shootings of any city in the state the last two years (14 as of last week), Sirkka says he has never had to fire his gun at anyone, nor anyone at him. He wants it to stay that way.

Along with car-patrolling and being on call for anything, as we did on this night, Sirkka has also worked undercover for the Westminster PD, mostly in drug and narcotics.

“I’ve seen just about everything doing this job,” Sirkka said. “But it’s great. There’s good job security, good benefits. I know where I’m going to be the next day, the next month, the next year. In hockey, I never had that security. I never knew where I’d be going next. I loved hockey and still do, don’t get me wrong. I wouldn’t trade my career for anything. But, for me, I still get the adrenaline, and I have a bunch of guys and gals who I’m part of a team with, people I know I can count on in any situation, who will have my back. It’s like hockey in that sense. I’m just wearing a different uniform now.”

***

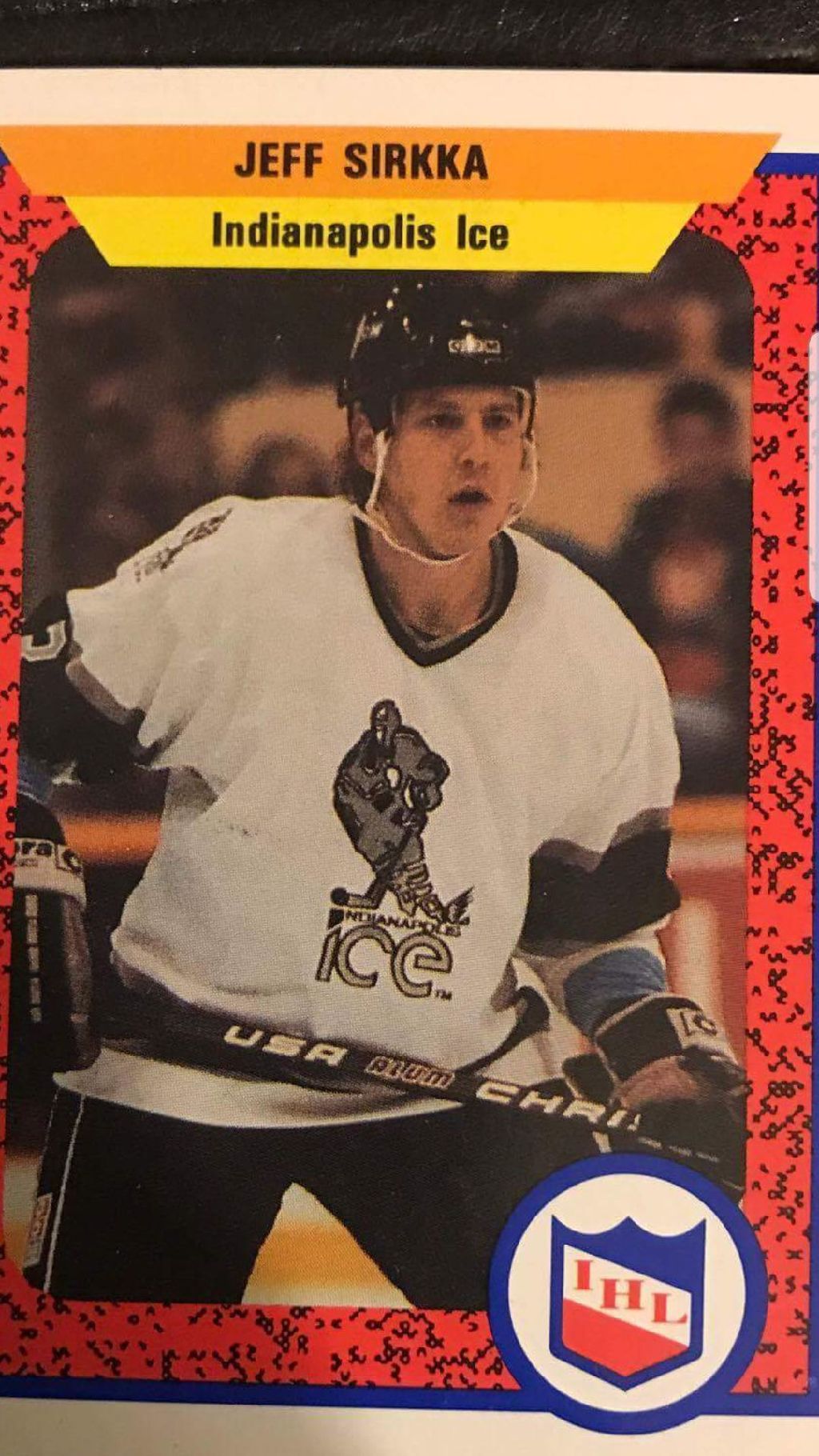

While Jeff Sirkka never actually played a game in the NHL, he came about as close as you can get. While a player with the Indianapolis Ice of the IHL in 1990, Sirkka almost made the Chicago Blackhawks (the Ice’s parent club) out of training camp. He was the last cut. But on Oct. 1, Sirkka was recalled by the Blackhawks. Defenseman Chris Chelios was banged up and the Blackhawks thought Sirkka could ably fill his spot if he had to miss some time.

For 10 days, Sirkka was officially a Chicago Blackhawk. He got NHL money, stayed in team hotels, practiced with the team, the whole nine yards. The only problem? Chelios kept playing through his injury, as did another D-man, Dave Manson, who was also banged up. Sirkka was on the team, but was a healthy scratch for all the games.

“I saw him many years later at some event, and I was like ‘Dammit Chelly, couldn’t you have just pulled the chute for one game at least, taken a night off?” Sirkka said.

After being sent back down to the Ice, Sirkka never again spent an official regular-season day on an NHL roster. He participated in training camps with the Boston Bruins, Vancouver Canucks and Washington Capitals, but never survived the final cuts.

At 6-foot, 193 pounds, Sirkka was a tough, stay-at-home defender who could move the puck on the power play some. A break or two here or there, and he could have had good-sized NHL careers like some of the defensemen whom he outlasted in the cuts in that 1990 Blackhawks camp.

Sure, Sirkka has a bit of “I coulda been a contendah” in him when asked if he is bitter over never playing in the NHL, but not much.

“I got paid to play hockey for 17 years,” said Sirkka, 50. “I saw a lot of the world, made a ton of great friends that I still have today. Not many guys can say that.”

He’s still close with several Grizzlies players, especially Derek Armstrong and Mike MacWilliam. While we’re driving around Westminster all night, MacWilliam checks in frequently over text. “You boys staying safe out there?” he asks more than once.

“Nothing but good things to say about that boy,” MacWilliam said. “Great teammate, and a great heart.”

***

This night turns out to be a fairly quiet one. It started out with a car accident, a fairly minor collision that nonetheless required lots of paperwork time for Sirkka, as it happened in his precisely defined beat area of the city. There are a couple of “suicide calls”, including one in which a man supposedly is threatening to jump off the bridge over I-25 and 136th Avenue. By the time Sirkka can put the car in blue-light, turbo mode, however, dispatch says the man has thought better of it, at least for there and the time being. The other involves a 14-year-old male who has apparently threatened this before. By the time we arrive, though, he is walking away with friends around him. Sirkka sees no need to interject.

We are called to a strip mall where a clerk called about a man being a “nuisance” outside. Another officer is there on the scene when we arrive, however, and an older, disheveled looking man talks quietly, saying he’s just hanging out and has a place to stay otherwise.

“Stay under the radar,” Sirkka tells him as he drives off. “No need to call attention to yourself if you don’t need to.”

Sirkka has seen a lot of disturbing stuff in his 16 total years as a cop. He’s seen headless bodies. He’s seen some of the lewdest and lascivious acts imaginable. Believe it or not, he’s seen a surprisingly high number of dead bodies sitting on a toilet seat (mostly men, he says – “Upper GI bleeding when they go”). Like the monotone female voice of the dispatcher alerting him to things like suicide calls, Sirkka has that “Nothing can surprise me” attitude and demeanor most cops have. But when we drive by the Jessica Ridgeway Memorial Park on 10765 Street in Westminster, Sirkka’s voice drops a few notches in tenor. Ridgeway, a 10-year-old girl in 2012, was kidnapped walking on the sidewalk of the park now named after her, her dismembered body found days later in Arvada. A 17-year-old boy, Austin Sigg, confessed to the murder.

“I have a daughter who was close to her age at that time,” Sirkka says quietly.

***

With not much going on, Sirkka “runs some plates” at various locations, usually big-box store parking lots and hotels. Equipped on the back of his car are two cameras that, amazingly, can zero in on any and every license plate it sees, no matter how fast he’s going. If there’s an outstanding violation of any kind associated with the license plate, an audible siren alerts Sirkka on the laptop computer in front of him and up pops all that car’s information and all the information of the driver to which the car is licensed. It’s truly Big Brother stuff.

Sirkka gets several alerts, but most are for stuff that is too minor for him to worry about, things like expired licenses from another jurisdiction, that kind of thing. There is one that pops up, though, on a car entering a King Soopers parking lot that makes Sirkka follow it and consider approaching the man who walks out of the car and into the store. It’s basically a misdemeanor for some minor infraction, where he lives in Denver.

The man notices us and does a double take, but walks swiftly into the store with a bit of a tough look on his face. Sirkka decides to let it pass. The young man had no idea, probably, just how close he came to getting picked up. The computer takes in all this information, though, and chances are he’ll get picked up soon enough, somewhere in Denver.

With activity slowing down even further as the hour gets closer to 2 a.m., there is time for Sirkka to pull over at an intersection and, while always keeping one eye on the scanner, have some good guy talk – about old girlfriends, old hockey teammates, old stories – but also plenty of talk about being a 50-something in the year 2018. He knows of many ex-players who fell upon hard times.

“I could have been one of them,” he says. “I know there isn’t a whole lot separating me from some of the people we’ve seen on the street tonight. I was lucky I found another calling. To me, I’m as proud of this, and probably even more so, of anything I ever did in my hockey career.”

Comments

Share your thoughts

Join the conversation