© 2026 ALLCITY Network Inc.

All rights reserved.

Since I began writing about baseball in 2013, and for the six years that followed, whenever I was asked the semi-regular question about who was the most underrated player in baseball, I never hesitated in my answer: it was DJ LeMahieu.

It was.

As the fates would have it, LeMahieu became a free agent after the Colorado Rockies most successful campaign in a decade and spent most of the offseason between 2018 and 2019 asking for a contract he deserved, but would never get.

As all 30 teams in MLB were refusing to give him more than the two-years, $24 million for which he would eventually settle, Colorado went in a new direction.

Not wanting to risk the possibility of waiting all winter and holding back their entire offseason budget only to have another team finally cave, and leaving them with nothing, the Rockies instead spent what they had on Daniel Murphy.

This, as it turned out, would be especially painful for Colorado fans who have now seen the two worst seasons of Murphy’s career (by far) while watching LeMahieu seemingly flourish into one of the best players in baseball – balling out in the Bronx.

Under the bright lights of The City That Never Sleeps, LeMahieu’s under-the-radar personality and play-style were suddenly thrust into the limelight. The city of Gotham lit up for a man with a bat and his signal soared across the sky.

He is a secret no longer.

But is that just because far more people are paying attention now? Is it because he has become a much better ballplayer?

Is it because he is with an organization that has managed to unlock the potential that Colorado could not or put him in a better position to succeed? Is it because right field is now 14 feet away?

Let’s dive into the details.

While it is true that more fans and media translate to receiving more credit for the same deeds, it can also often mean that you get more blame. It isn’t debatable that the move to the Big Apple has helped LeMahieu’s case nationally, but it is also still absolutely true that had he wilted under that added pressure, we would not be having this conversation.

At the very least, it’s clear he hasn’t failed in that capacity.

According to the advanced metrics of both FanGraphs and Baseball Reference, the 32-year-old is better than he’s ever been.

He set a new standard for himself in wRC+ (136) and OPS+ (135), besting his 2016 marks of 130 and 128, respectively. Naturally, this resulted in his top totals of 5.4 fWAR and 5.9 bWAR.

Those are both a full win higher than what he managed in 2016, his all-around best year for the Rockies.

He also won the NL batting title that year by hitting .348 and putting up a career-high .416 on-base percentage. (He did post a .421 OBP in 2020, but I’m not sure if you heard… they only played 60 games.)

In his “breakout” season of 2019, wearing the most classic of pinstripes, he hit .327 and on-based at a clip of .375, both very impressive and less than his best. Which is where we come to the third part of the standard triple-slashline: slugging percentage.

Again, 2016 was the peak of LeMahieu’s slugging in Colorado, hammering out a solid mark of .495. Considering he has largely been a slappy-singles-guy that managed only 11 round-trippers that season, it was quite the accomplishment to hit the 32 doubles and eight triples he needed to add the power element to his game.

In 2019 with the Yanks, he hit 33 doubles and two triples.

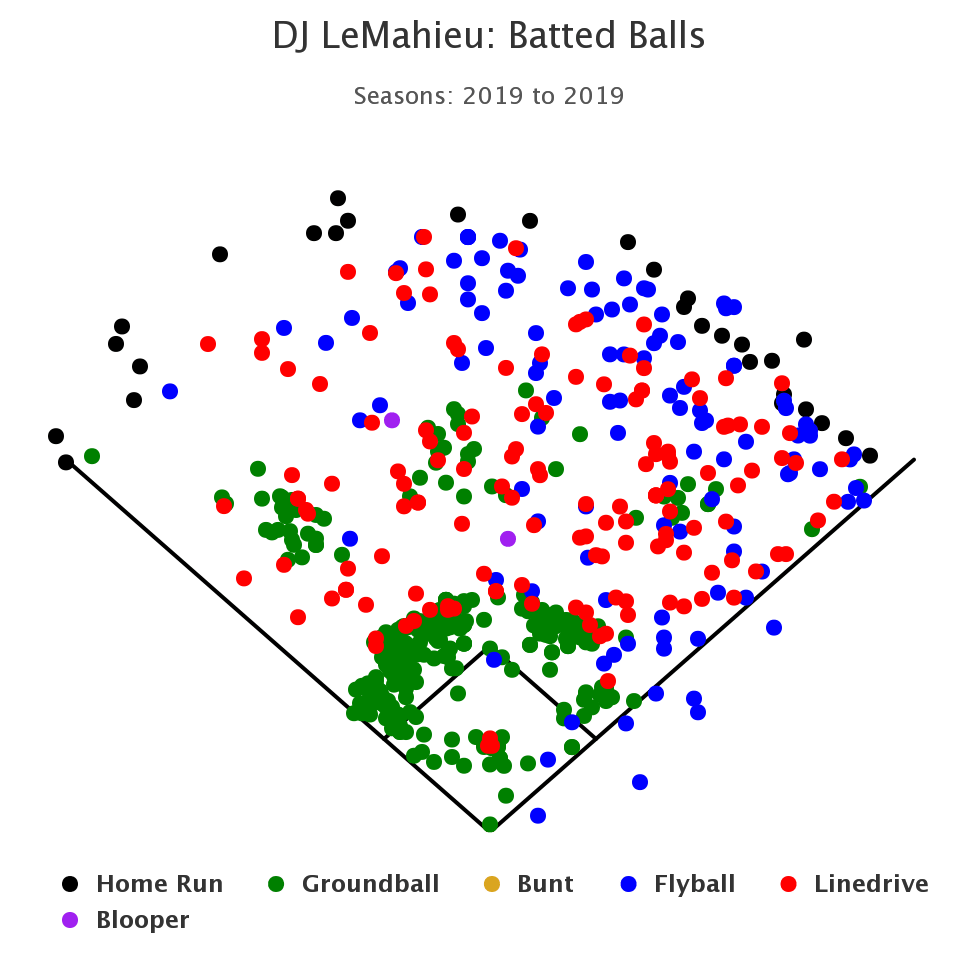

Those of you schooled in the ways of deductive reasoning have likely already reached the conclusion that this leaves us at the longball. Immediately destroying his career high of 15 homers in Colorado, DJLM went yard 26 times (in the regular season) his first year in his new home.

You might be tempted to conclude that this happened because LeMahieu joined a Yankees club that has embraced the 21st century. An organization of coaches and analytics department that removed any restrictions placed upon him in Colorado and unleashed a power hitter who had been lurking beneath the surface all along.

So, did he join the Launch Angle Revolution?

If he did, it was more as a pamphlet writer than as a fighter on the front lines.

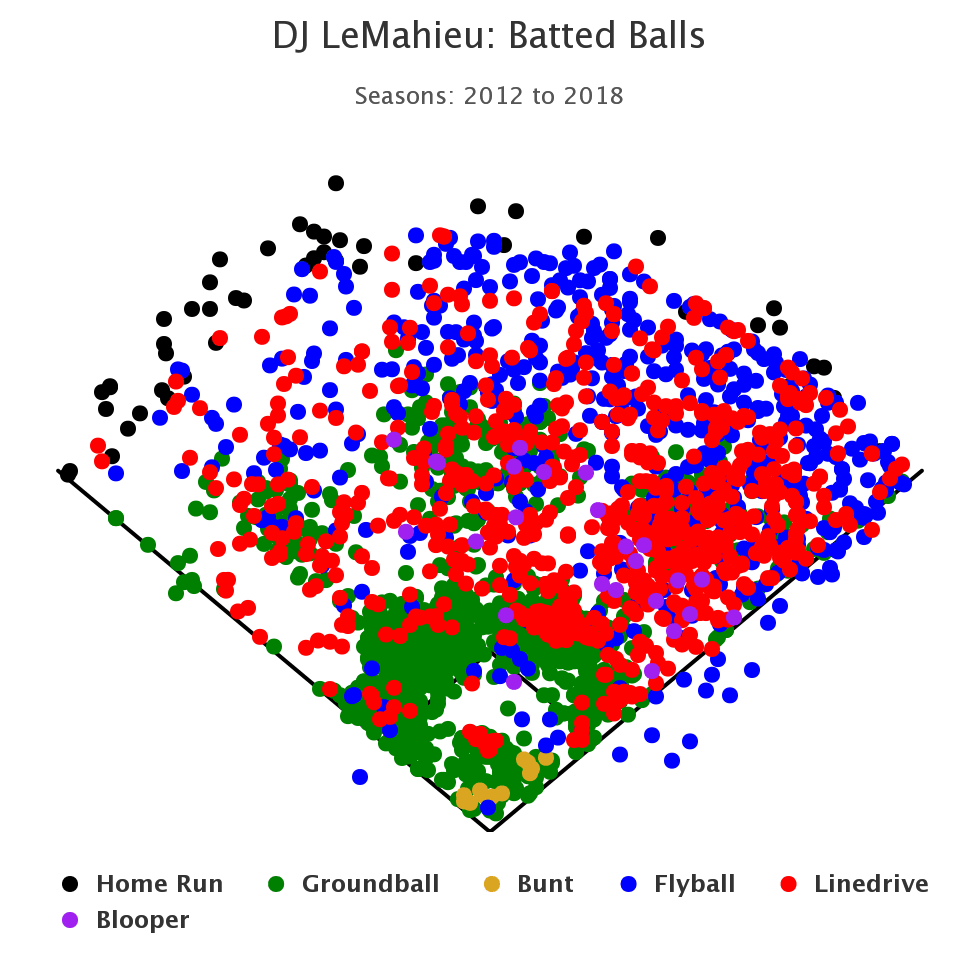

His fly ball rate of 26.2 percent in 2019 was the second highest of his career, but was down from 29.5 percent in Colorado the year before. It’s also not that far off from the roughly 23 percent marks he put up in 2014 and 2016.

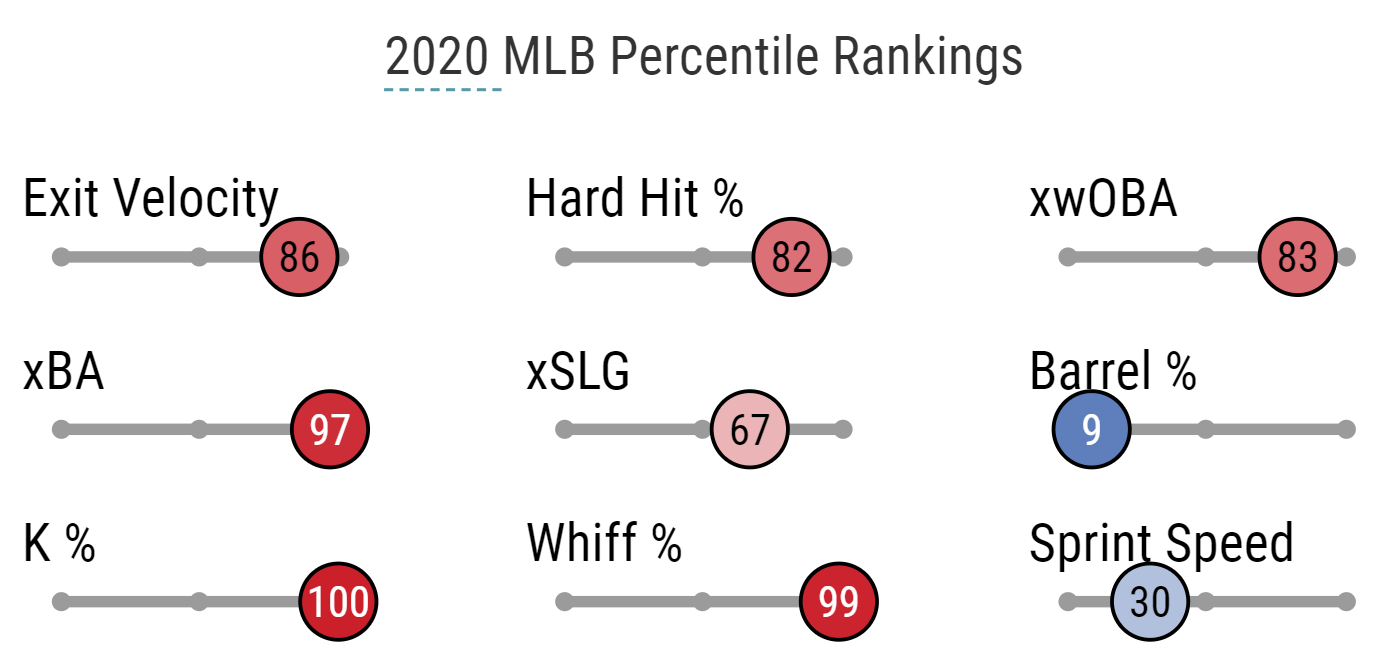

And in this strange year of 2020, he still managed to hit 10 homers in just 50 games despite a 21.1 percent fly ball rate.

His highest line drive numbers come in 2015 (26 percent) 2016 (26.6 percent) and 2017 (24.7 percent) compared to 23.7 and 22.3 percent so far in New York. His ground ball numbers, however, remain remarkably consistent.

At the most extreme points in New York, LeMahieu is hitting the ball in the air about three percent more often than he did in Colorado.

If the gurus in the Bronx didn’t help create a new trajectory off the bat, did they do something to unlock extra velocity off it?

Once again, there is almost no evidence of it.

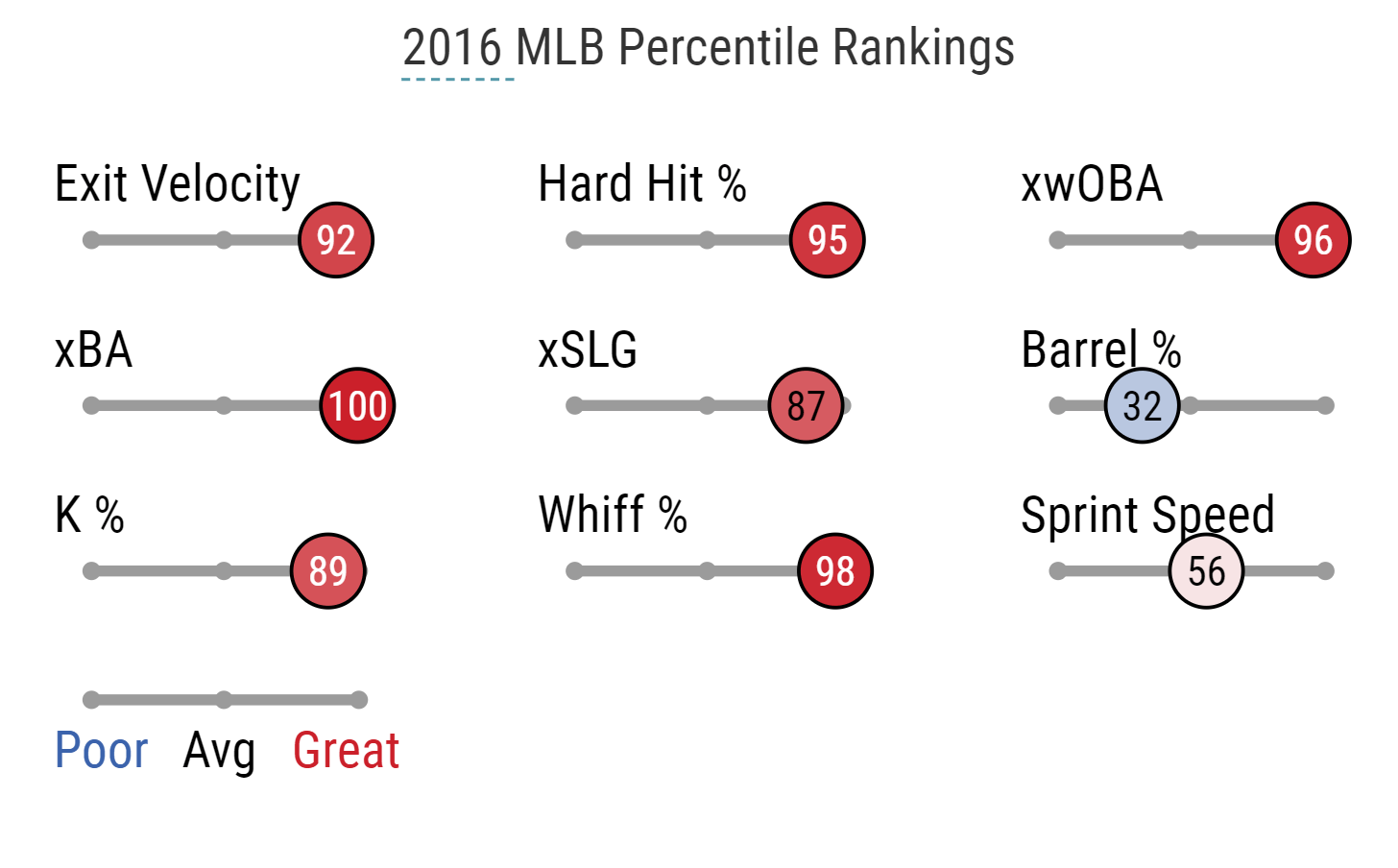

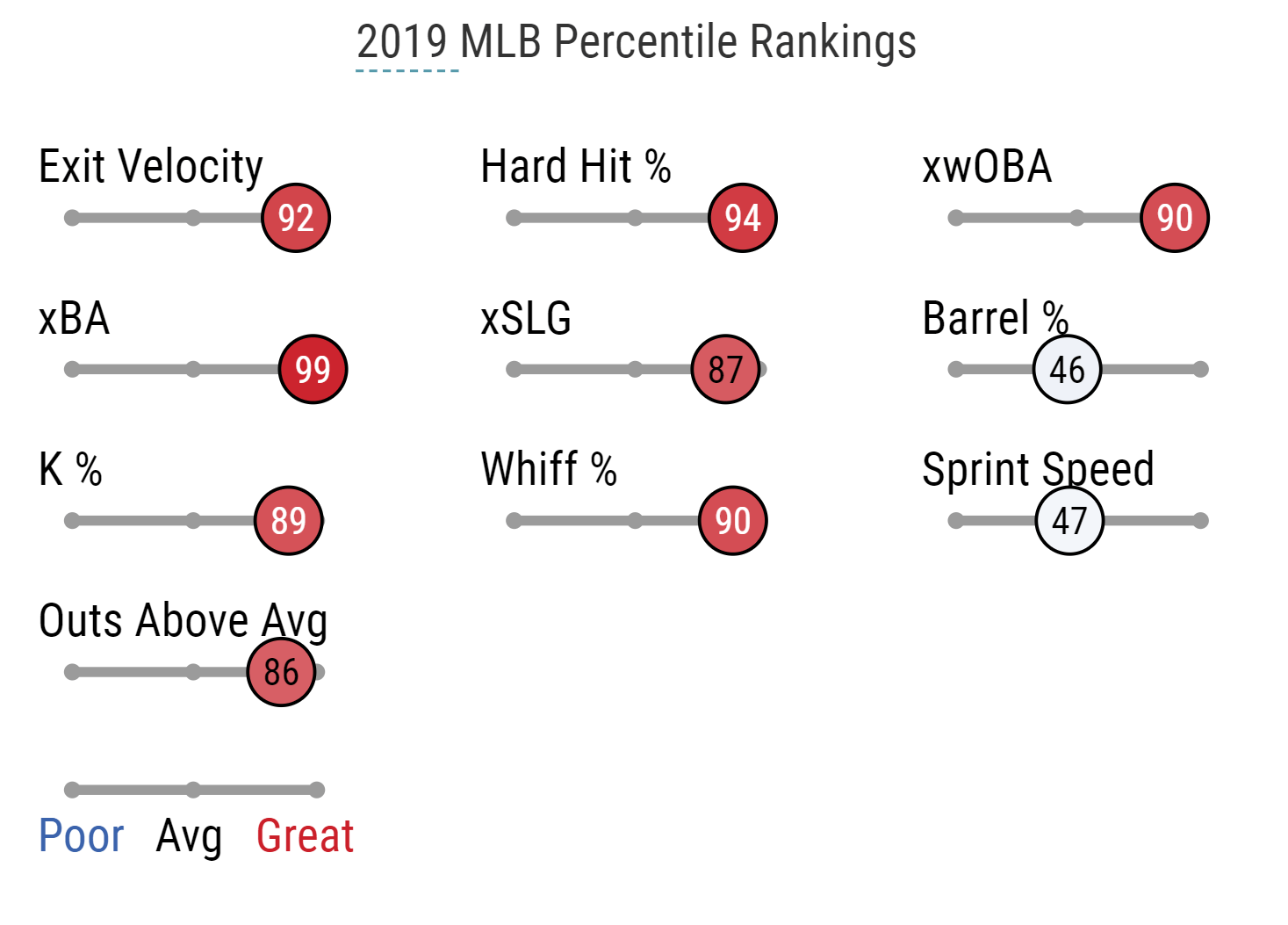

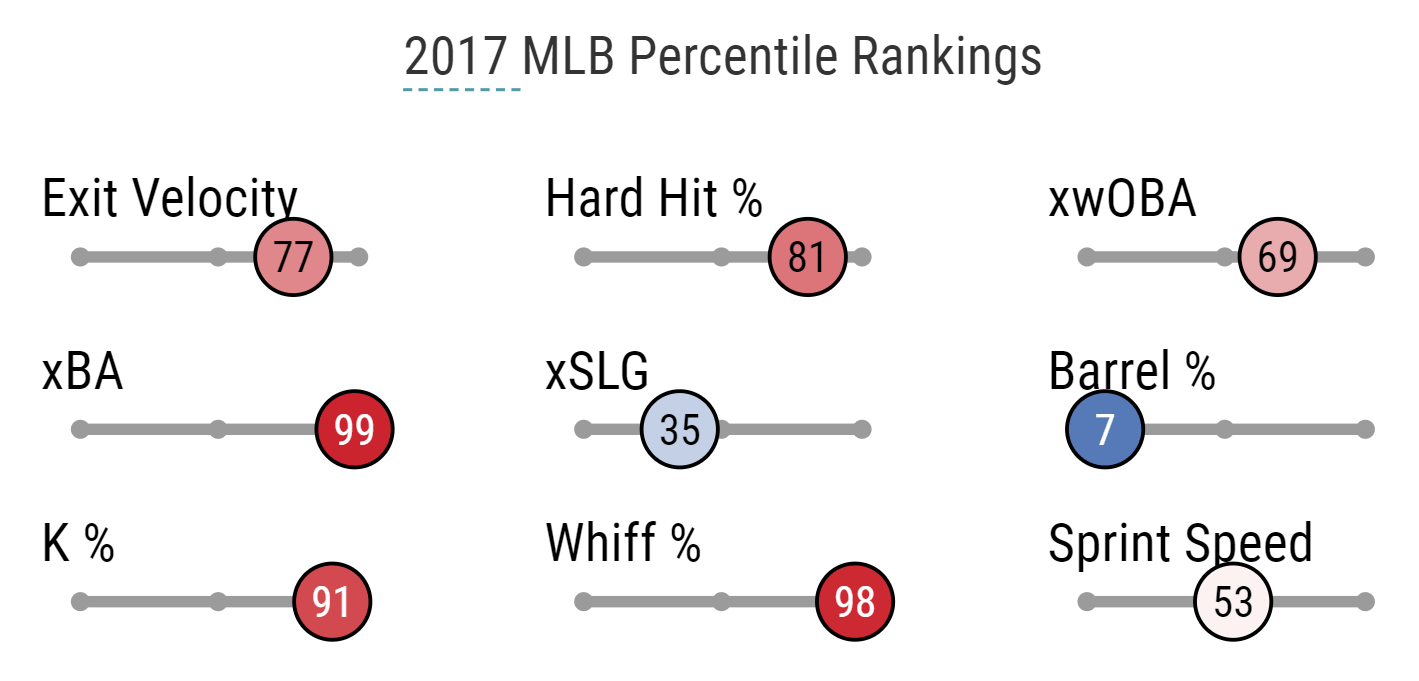

Let’s compare his two best seasons using the StatCast data:

In Colorado, he was hitting the ball as hard if not harder, swinging and missing less often, and was expected to have a wOBA (weighted on-base above the average) six points higher than what he accomplished in New York.

This statistic is still the best indicator we have for how a player would perform in a neutral environment.

In short, LeMahieu’s process was either the same or better at the plate in 2016 as it was in 2019 with the one exception being “barrels,” a category that requires just the right combination of exit velocity and launch angle.

This is the best piece of evidence in the argument that there has been a change in LeMahieu’s game.

He isn’t hitting the ball harder more often. And he isn’t hitting the ball in the air more often. But he may be hitting the ball hard and in the air at just the right angle more often.

So explain this:

DJ may be well on his way to some accolades in 2020 for being one of the best all-around hitters in the game. In a small sample size of 50 games, he managed to crack another 10 home runs despite a nine percent barrel rate. Compare that to 2017 where his seven percent barrel rate and .310 batting average combined with still great hard hit rates and exit velocity to only result in eight home runs in 155 games.

His nine percent barrel rate from this year is also significantly lower than his 32 percent mark in Colorado in 2016 when he launched just 11 homers in 146 games. And his expected slugging was better that year at the Mile High as well. But still… a far better home run rate on the East Coast.

These stats are telling us that if there has been a change in the approach at the plate or the rate at which LeMahieu is making that perfect sweet-spot contact, it has been so minuscule that it can’t possibly account entirely for the dramatic jump in home runs.

During his time in Colorado, LeMahieu topped out at a home-run-per-fly-ball rate of 11.1 percent. Only twice in his purple pinstripe days did he get into double digits. For the Yanks? 19.3 percent and a whopping 27 percent.

So let’s get to the part you all knew was coming and suspected was a massive part of the puzzle but still may end up a bit baffled by.

The ballparks.

It’s not just that LeMahieu is hitting the ball out of the yard more often, it’s where he is hitting the ball out that needs to be front and center in this conversation.

From 2012 to 2018, while playing for the Rockies, LeMahieu hit seven opposite-field home runs. One per season.

In 2019, his first year in New York, he hit 16:

That is a monumental difference which cannot be accounted for by tenths of percentage points in angle and velo.

We do have to note that these charts do not reflect only Coors Field and Yankee Stadium but of all his batted balls for both teams. We should also further note the ballparks of in his new division, specifically Boston and Baltimore, also have much shorter porches in right field than his previous division, such as San Diego and San Francisco.

In case you never saw him play in Denver and are wondering if taking the ball the other way is a new phenomenon for him… nope. He actually went “oppo” more often from 2014-2017 than he did in 2019. But it has always been his methodology, taking the ball to the other way a at 35.2 percent clip in his career.

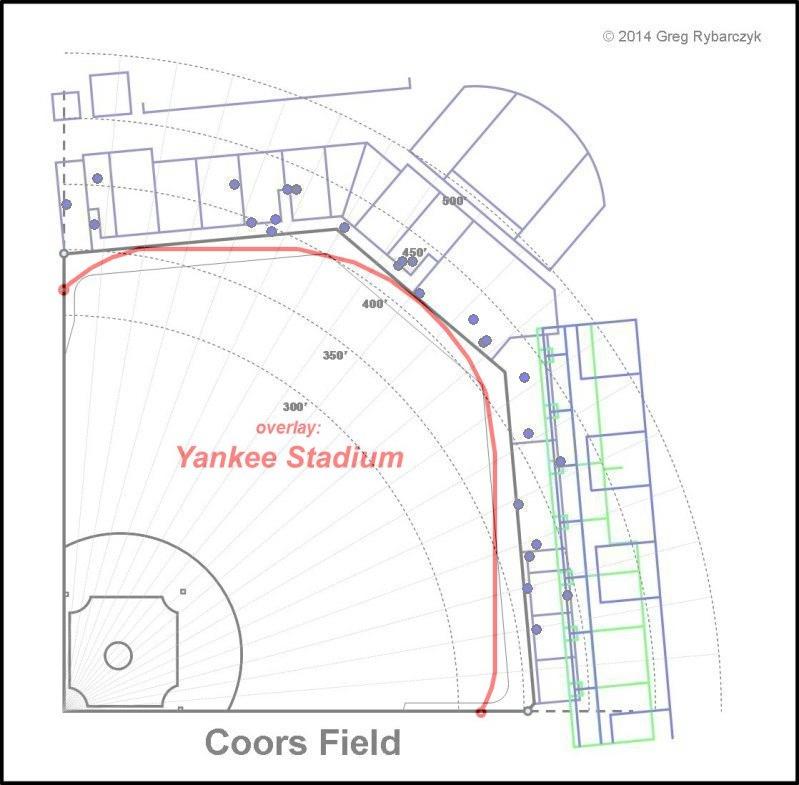

So maybe this all has something to do with this:

At 20th and Blake, right field is 350 feet away at its closest and features a 14-foot high wall that now stretches all the way to center field.

At 1 E 161st St, right field is 314 feet away at its closest and features only a nine-foot wall.

That seems like a much bigger distinction than anything we’ve uncovered in the peripheral statistics thus far. The air ain’t that thin in Denver. And since the implementation of the humidor, Coors Field hasn’t led the league in home run rates.

This from Manny Randhawa of MLB.com and StatCast:

“Coors Field has yielded the second-most homers (502) of any ballpark (since 2015) behind only Yankee Stadium (542). But as it turns out, there are eight ballparks with a higher percentage of homers that weren’t either barreled or solid contact, led by Minute Maid Park.”

Boston and Baltimore, in the AL East right there with New York, also rank ahead of Colorado in cheap home runs surrendered.

Now comes the part where I assault the eyes of all Rockies fans and just roll the tape:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O_pINnX8x6E

We can’t say for sure exactly how each of these fly balls would have played at Coors Field, or more generally in NL West ballparks. However, it appears that of the 14 opposite-field homers he hit at Yankee, maybe one would have gone out at Coors. Five in total would likely have still been hits; nine would have been easy outs and another two were probable outs with decent defending.

Two more opposite-field longballs came on the road (Baltimore and Houston) and both of those would also have been easy outs at any of the NL West ballparks.

This translates to 11 home runs that would not have escaped his old stomping grounds – and would have been outs – and four home runs that would have been doubles just two years prior. That accounts for 94 percent of his oppo bombs and 62 percent of his overall home runs.

When 11 outs and four doubles turn into home runs, slugging percentage and batting average and on-base and wRC+ and OPS+ and fWAR and bWAR are all going to benefit greatly across the board.

You can’t just not give him credit for hitting all those homers, though. In Denver, those are outs that don’t help his team at all. In New York, some of these were literal game-winners. That’s real value.

It just doesn’t have anything to do with DJ LeMahieu becoming a better player.

Can we really say he’s 30 percent better at the plate and several full wins more valuable in New York?

By the results, perhaps. He has been a more valuable player for the Yankees than he was for the Rockies. But he hasn’t been a better one; a distinction with all the difference in the world for recognizing the true talent of underrated Colorado hitters.

You can find this same dynamic at play in the post-Rockies’ careers of Larry Walker and Matt Holliday and less star-level hitters like Juan Pierre and Dexter Fowler. For roughly the same – or often even less – production, they are given far more credit by stats, fans, and media. They get more accolades, attention, and money.

It fosters an environment where Colorado has to pay an extra tax in free agency for both hitters and pitchers, can rarely receive fair trade value for their players (if ever), and almost always have their young guys and farm system underrated.

This narrative created a scenario where one of the 10 best right-fielders of all-time couldn’t get into the Hall of Fame until his final opportunity and, even then, just barely.

Would you purposefully choose a job that is much harder than your current one, for which you will not even get full credit for your work? Maybe if the pay was right?

If given the choice, as LeMahieu was, wouldn’t you rather be in a place where winning a batting title is treated like history and not like a travesty?

The Yankees should get credit not for unleashing a new version of LeMahieu, but for rightly recognizing that he was the perfect fit for their home field environs. (Y’know, and then being so confident that they signed him to a middling contract for a bench role after spending most of the offseason chasing Manny Machado.)

While he’s always been a great ballplayer, no matter where he played, at least he isn’t underrated anymore under those bright lights of Yankees Stadium.

Let’s just be clear on this…

The Yankees didn’t unlock some hidden potential in DJ LeMahieu.

Their ballpark did.

Comments

Share your thoughts

Join the conversation