© 2026 ALLCITY Network Inc.

All rights reserved.

The Colorado Rockies made only one trade in the days approaching the July non-waiver trade deadline, landing some much-needed relief support in Seunghwan Oh from Toronto on July 26.

Since his acquisition, the necessity of his presence has become even more apparent. The Rockies have already lost in three games on walk-offs in August. Closer incumbent Wade Davis is on pace for his highest worked season since he was still a starter, and the weight on his shoulders has shown in a gradual velocity decline over the season. Apparent workhorses Chris Rusin and Bryan Shaw have both struggled and dealt with health issues, leaving essential innings in the bullpen up for grabs.

For the Rockies, The Final Boss might be telling opposing teams that Peach is actually in Wade Davis’s castle, but the all-time Korean Baseball Organization saves leader is still going to play an important role as the team fights fatigue and a never-ending schedule of contenders as they fight for a playoff berth.

Here’s how Oh has been effective in his first week with Colorado and in the past, and how he’ll try to find success going forward.

Makeup and arsenal

Oh is 5-foot-10, and doesn’t get the same leverage and torque from his shorter frame than Davis or Ottavino, both of whom have seven inches on their new bullpen mate. Because of this, he uses every ounce of his conservatively-listed 205 pounds to generate momentum and deception.

Despite being listed as the same height and weight dimensions as former Rockies closer Greg Holland, the two pitchers work very differently. Where Holland is very much a two-pitch, come-straight-at-you with velocity and a hard slider, Oh is similar to many of the pitchers imported from Korea and Japan in that he will change speed and pitches and use his mechanics to keep the hitter from getting properly extended and barrel the ball.

Here’s a clip from his first bullpen session after signing with the St. Louis Cardinals in 2016:

Albeit Oh is not throwing 100 percent in this session, but you can still note his mechanics. On the more orthodox side, he hides the ball well until release, hanging his throwing arm and hiding it behind his torso until it suddenly appears as he begins to torque his hips. This helps hide a release point that can be inconsistent across his pitches at times.

But it gets interesting is with his lead foot. Watch as it taps the ground as he prepares to drive forward. This is similar to Tyler Anderson’s hitch in his delivery, except Oh actually goes all the way, whereas Anderson keeps his foot in the air. The effect is the same though, adding a slight delay that throws off the hitter’s timing.

With this delivery, he throws a full toolbox of pitches—up to six depending on what tracking system is in use. This is common of pitchers imported from Japan or Korea, being able to pull out any sort of pitch in any count to keep hitters guessing. While he primarily uses the trio of a four-seamer and cutter/slider combo, he will change up speeds with a curveball and every once in a while tie in a traditional changeup, slider and sinker from time to time to manipulate speed, break and location.

Mixing his fastball that will sit low 90s with a cutter in the mid-80s and a curve that can dip into the 60s, Oh generates a lot of strikeouts and weak contact simply by spreading velocity across 25 mph at times. He does induce more fly balls than grounders, but we’ll dive into why that might not be as big of a deal for him as it might for other pitchers later. It also certainly helps that he gets enough whiffs and can spot on the edges well enough to rack up a K/9 regularly above 10.

Fastball

If you’ve read any of our previous Film Rooms on pitchers—or are even vaguely familiar with the sport of baseball—it shouldn’t surprise you to hear that the fastball is Oh’s No. 1 pitch. Additionally, also like most pitchers in the game, the four-seamer is not his out pitch, but instead sets up his other pitches, although this concept does get rarer with late-inning relievers like Oh.

Still, according to Brooks Baseball, no matter the count, the odds are greater than 50 percent that a fastball is coming. It can have some sinking action, especially low and in on righties, and is recorded as a sinker occasionally.

Regularly sitting 92 mph, he can reach back and get up to 94 and very occasionally 95. Its usage is highest early in the count, jumping up to 80 percent on first pitch against lefties, but its effectiveness as a pitch increases in the middle counts, with whiff percentages jumping anywhere from 4 to 10 percent before two-strike or three-ball counts—where the hitter goes into defensive mode—from Oh’s average.

He likes to live in the top of the zone with it, mostly to set up his cutter and slider, but it also compounds on itself, paving the way for swings and misses from velocity and eye level changes.

This is about the best case scenario:

Oh embarrasses Andrelton Simmons, who is clearly hunting a pitch much slower, making a 93 mph faster look like 100.

Here’s another example, striking out Dexter Fowler in Oh’s second appearance for the Rockies:

Fowler is fairly significantly behind on a fastball that moves slower than a Jon Gray slider. While a part of this can be attributed to Fowler’s struggles this season and the late movement on Oh’s fastball, it’s also a testament to the rest of his pitches.

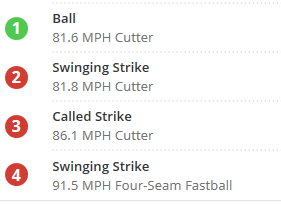

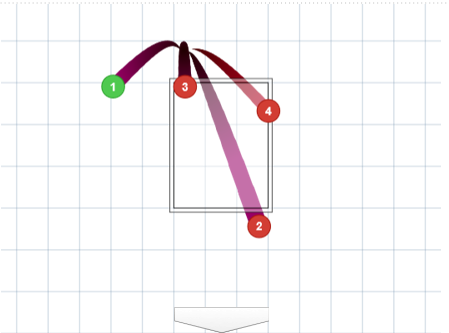

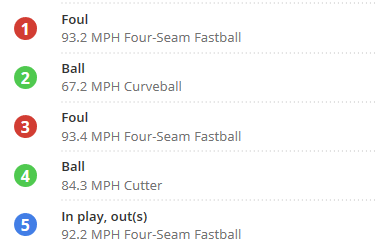

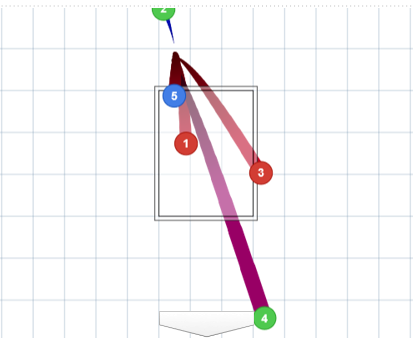

Take a look at the sequencing and location from this at-bat:

The simple velocity change of five mph from the previous pitch and 10 from the first couple of pitches of the plate appearance makes the final pitch look like a bullet, despite being a slower-than-average fastball.

All of Oh’s pitches play off of each other, with his cutter/slider the glue that holds it all together.

Cutter/Slider

Oh’s “secondary” pitches are his bread and butter. While he does throw the fastball the majority of the time, he throws his cutter/slider 31.3 percent of the time, at some points encompassing the majority of an at-bat, as we saw in the Fowler example. As his go-to pitch, we’re going to spend the most time talking about it.

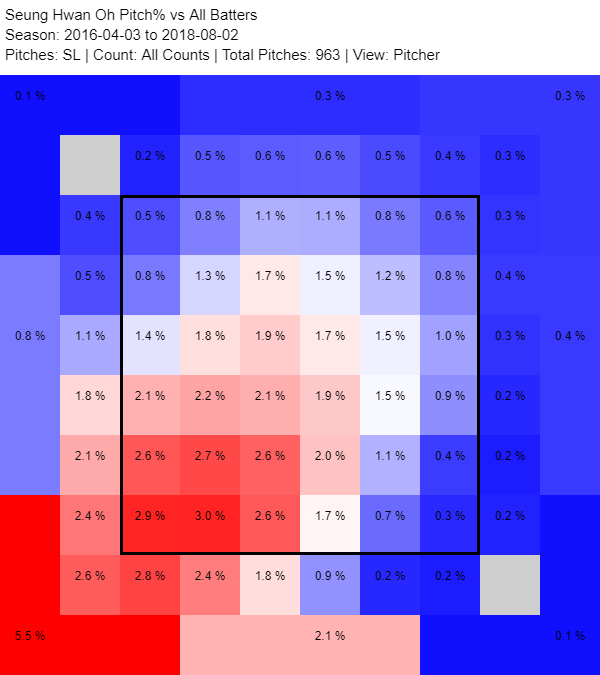

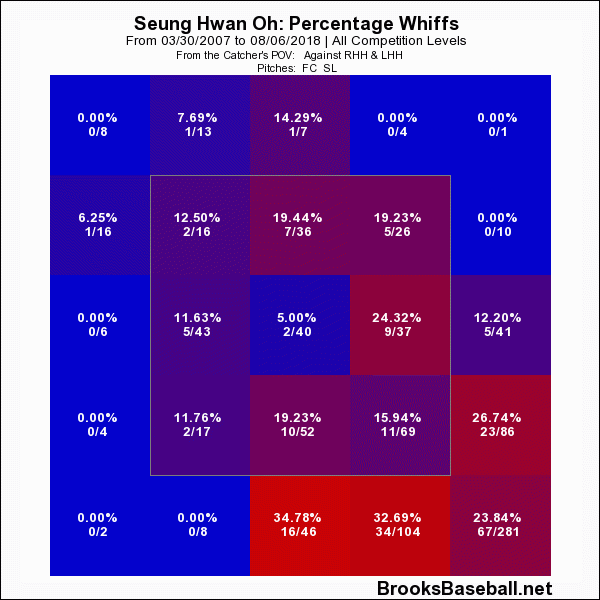

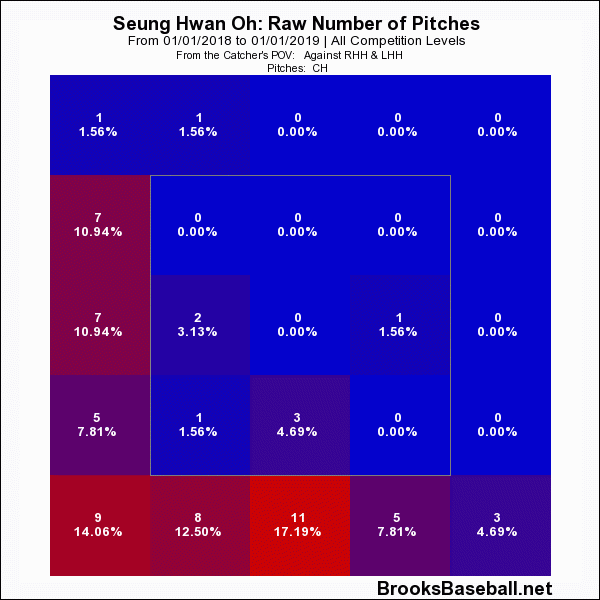

Identifying Oh’s pitches gets tricky when he starts throwing his offspeed. Brooks Baseball does not even recognize that Oh throws a cutter, and labeling the two can be ambiguous and subjective. Oh manipulates the speed and break to make them unpredictable, so the rule of thumb is the slower it goes and more break it has the more it gets registered as a slider, and the faster it goes, the tighter its break and it gets called a cutter.

This doesn’t exactly address sliders that don’t break as much as they should, giving us lower velocity cutters that probably weren’t intended to be. Point being, there is some margin for error.

Fortunately, the two pitches are utilized similarly enough that we can get away with discussing the two pitches in the same vein.

While the slider is very exclusively used low and to the glove side, breaking away from righties and in to lefties, the cutter is used all over the place. The jump in velocity and strong late break means it can catch right-handers fly fishing like a slider and also lock them up inside. In the same way that Ottavino mixes up his offspeed, so does Oh, allowing it to be a weapon all over the strike zone.

As is typical with sliders, it’s most effective low and to the glove side, drawing a lot of swings and misses, particularly out of the zone.

But for as many strikeouts as the breaking ball contributes to, its late break makes it a hard pitch to barrel. When a hitter gets their timing down and sees it well, it can be squared up. However, if the conditions aren’t perfect, it can be hard to recognize. Take a look at this clip of Oh striking out Paul DeJong again:

This pitch catches a lot of the strike zone, and it’s traveling only 81 mph. It’s a two-strike count in a tie game in the eighth inning with no outs. If there ever was a time to take a defensive approach in the box, it’s on this pitch. As a heart-of-the-order bat in what could be your last plate appearance in a close game, you don’t want to go down on the pitcher’s terms.

Still, it looks like DeJong never even thought about swinging at this pitch. Plus, he walks back to the dugout immediately, with no doubt in his mind it was strike three. This shows how much late action the pitch has, with the ability to become an obvious strike after looking like a ball for 58 feet.

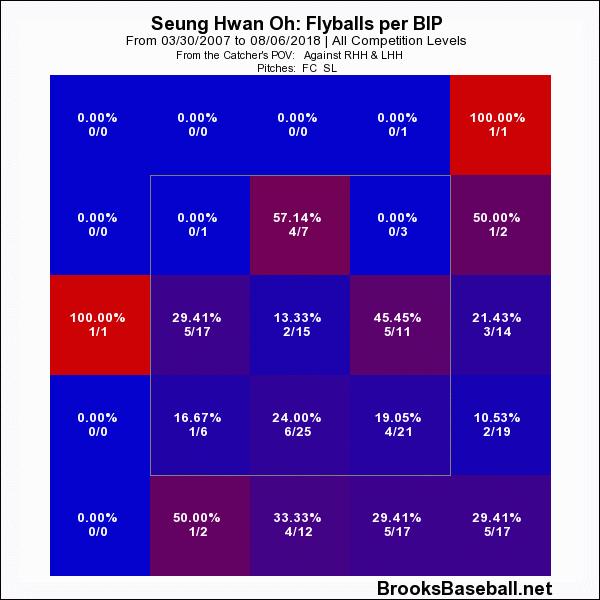

While the late break can do things like this from time to time, where it really comes into play is on balls put in play. Here’s a fly ball rate on the breaking ball by pitch location:

Up in the zone and below it, hitters will put the ball in the air. In 2016 and 2018, Oh kept his fly ball rate overall on the slider/cutter below 30 percent, and in 2017 when he struggled to a 4.10 ERA it jumped above 40. Typically, balls in the air mean more trouble, and that is true for Oh to an extent.

But the late break lets him get away with it on occasion thanks to two forms of deception: velocity and location.

From the simple velocity change, hitters can recognize early that it isn’t a fastball and is going to have some break. However, if the pitch holds off on tailing until the last moment, the hitter’s adjustment can put their swing plane under the ball prematurely and make them pop it up, especially if the velocity is still putting them out on their front foot.

Jed Lowrie is a bit in front of this pitch out and a little low, pulling it just to the right of second base in center. He also gets a pretty steep launch angle out of it, which is pretty impressive on a pitch in that spot.

It’s my suspicion that this is a product of that late break. It looks like Oh is trying to backdoor a strike call like he did in the DeJong at-bat, with similar action. But because Lowrie is out in front, the ball isn’t into its dive yet, and he lifts it. He also doesn’t hit it very hard because its difficult to get the full strength of your swing behind a ball away and if you’re timing is a little ahead.

Even when the ball is barreled up, it might not necessarily go anywhere on his breaking ball when it’s low:

In both of his good seasons in MLB, Oh’s batting average allowed on fly balls and line drives is around 100 points better than the league average in MLB: in 2016 the league hit .411 in such situations but .297 off Oh, and this year the league is at .403 versus Oh’s .316. This year in particular, it’s coming from a hard hit rate on fly balls that is seven percent lower than the league average, per FanGraphs.

Oh’s main breaking ball does well enough to keep hitters off balance with varying speeds and break to make the fly out a viable option for him. As for how that will play in Coors Field’s spacious outfield, so far so good in his lone inning at his new home park, but it could spell trouble in the future.

Curveball and changeup

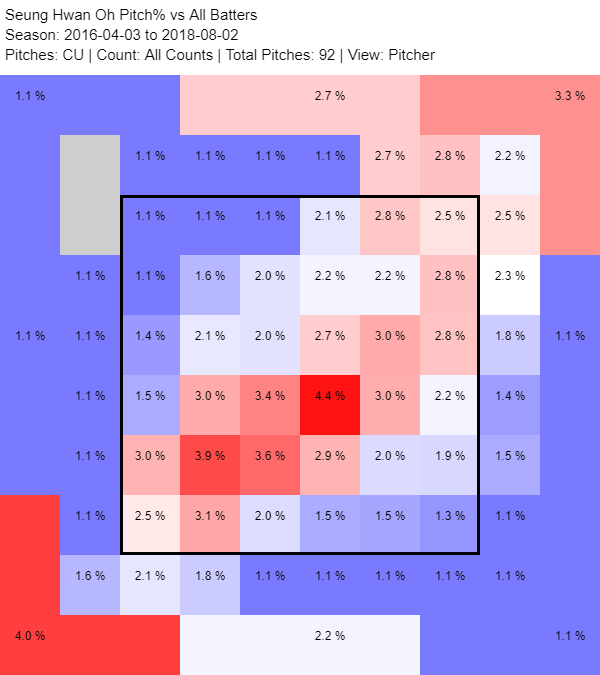

The curve is Oh’s third most used pitch, but according to Baseball Savant, he only throws it 5.6 percent of the time.

It mainly serves to change speeds and eye level, but is definitely a “get me over” pitch. In his career, batters are hitting .316 off it and he’s only recorded four strikeouts. He’ll spread it all over the plate, mostly with the intent to set up his breaking ball and fastball:

Full disclosure: I included this clip mostly because it floats in at 67 mph, making it the slowest he’s thrown in his career and even caught the St. Louis Cardinals broadcasters off guard. But, while it misses in location—as it will do semi-often—its low speed can make future pitches harder to evaluate.

He will get people to chase it on occasion, but very rarely throws it later in counts. When he does, it’s the change in speed that does most of the work, with the break as a secondary complement:

You can see that Dustin Fowler is pretty much right on this pitch location wise, but is out in front and swings through it.

The changeup is very similar in usage, sitting around 83 mph, though. It’s another pitch that gets knocked around when it’s put in play, to the tune of a .321 batting average over the course of Oh’s career.

In this same at-bat, Oh throws two changeups, neither of which is remotely close to the strike zone:

This is what he likes to do with it; miss the zone to avoid damage and use it to set up his other pitches. The first clip, which misses the outside edge at 84, preceded the curveball shown above, giving it a speed difference of -10. The second one came in before a cutter at 82 in the bottom inside corner.

The changeup is not a zone weapon for Oh:

The curve and change are both additional pitches that build up Oh’s fastball and slider/cutter. While they won’t make highlight reels on his strikeouts, they are integral in developing the pitches that do.

A case study in sequencing

Because the success of any individual pitch of Oh’s is dependent on the pitches before it, it makes sense to look at them in a collection. Here’s the at-bat against Matt Carpenter that included the molasses-like curveball:

Here’s how that looks in charts:

This is what makes Oh effective. He paints the black with his intent pitches and makes sure his setups are nowhere near the strike zone. The most hittable pitch in this at-bat is the first one, by design. If Carpenter doesn’t put that fastball in play, fouling it off (like he did) or taking it for a strike, he can begin his game of manipulation.

No two consecutive pitches are within eight mph of each other. Going hard away and then 26 mph slower on the same edge of the plate, then returning to that original speed on the inside edge is hard to keep up with. Then, drop in nine mph and see if you can get him to chase on something in the dirt. If not, great, he’s still playing catch up and a guessing game on when the next pitch is going to cross the plate.

Carpenter fares better than most on keeping in line with timing but is still victimized by the final pitch, hitting it straight up. No pitch is similar to the previous one, in speed or location. In this at-bat, he throws his best pitch, the breaking ball, only once, but still walks away with an easy out on a lazy fly ball. A lesser hitter without the discipline of the MVP-candidate Carpenter isn’t going to get bat on ball so well.

Conclusion

Oh gets his strikeout numbers and outs by making sure no hitter is comfortable in the box. By changing speeds and when and how his breaking ball moves, he keeps hitters guessing, with good enough stuff to get whiffs and poor contact when it is made. When he throws a pitch that he doesn’t want you to hit, it doesn’t come close to the strike zone, but he’ll follow it with a cutter that paints the edge.

In the purple pinstripes, Oh will have to continue being precise with his pitches of intent. The lazy fly balls will fall in for hits more at Coors Field. In Rogers Centre before his trade, a hitter-friendly environment was not an issue. The Rockies are banking on that to continue, with Oh’s acquisition extremely pivotal in giving them quality innings before Ottavino and Davis and resting an overworked bullpen that has sputtered as of late.

If he continues to perform well, picking up his $2.5 million club option for next season is a no brainer.

Comments

Share your thoughts

Join the conversation