© 2026 ALLCITY Network Inc.

All rights reserved.

On Wednesday night, Kyle Freeland recorded his sixth consecutive quality start, limiting the Los Angeles Dodgers to three runs in 6.2 innings, and although the Rockies would not provide enough offense to get him the win, he did his job and did it admirably. Again.

Freeland has kept opponents below four runs in eight of his 10 starts so far this year. Other than implosions on April 3 and 18, he has been one of the top pitchers in baseball.

He is tied for fifth in the National League in bWAR with Patrick Corbin of the Arizona Diamondbacks, and is behind only sure-fire All-Star Game candidates Max Scherzer, Aaron Nola, Jacob DeGrom and Johnny Cueto (who has made only three starts but was phenomenal in each), in that order.

The key for Freeland in his sophomore campaign has been getting the ball on the ground and letting the gold-dusted infield behind him do the work. So far, he is generating groundballs at a rate just below 50 percent of the time on balls in play, while only 17 percent of those are line drives. For context, the league average is 45.4 percent groundballs and 19.8 line drives, so both favor Freeland.

This was exemplified Wednesday night, as he recorded 10 outs on the ground to one in the air.

How does he produce not only these ground balls at a high rate but results, in general, that put him into the elite territory he’s been at so far in 2018?

Arsenal

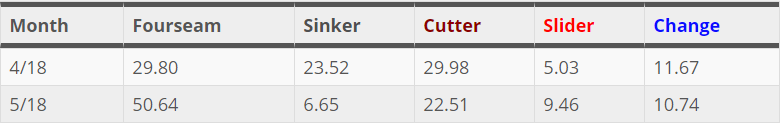

It all starts with the pitch mix for Freeland. He utilizes three forms of fastball—the traditional four-seam, then a sinker and a cutter. He complements those with a changeup and a slider. Here’s his pitch usage percentage by month this season:

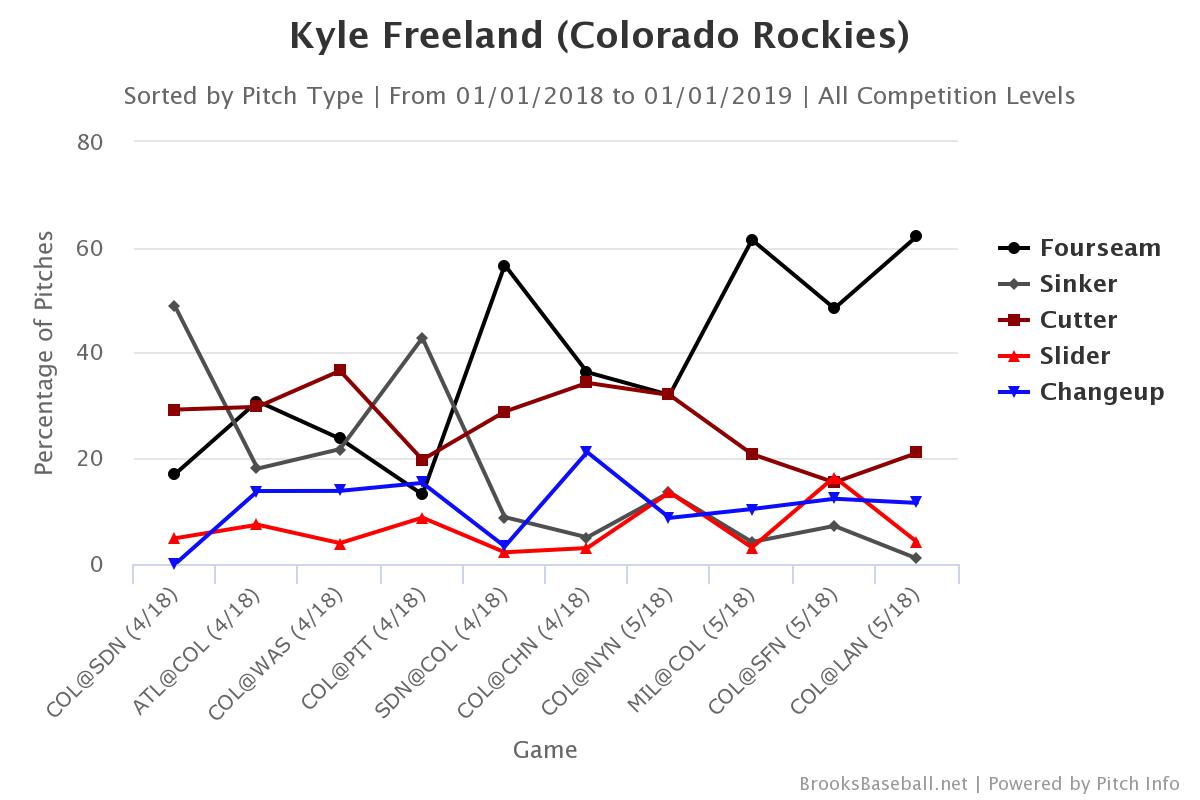

And his usage per game this year:

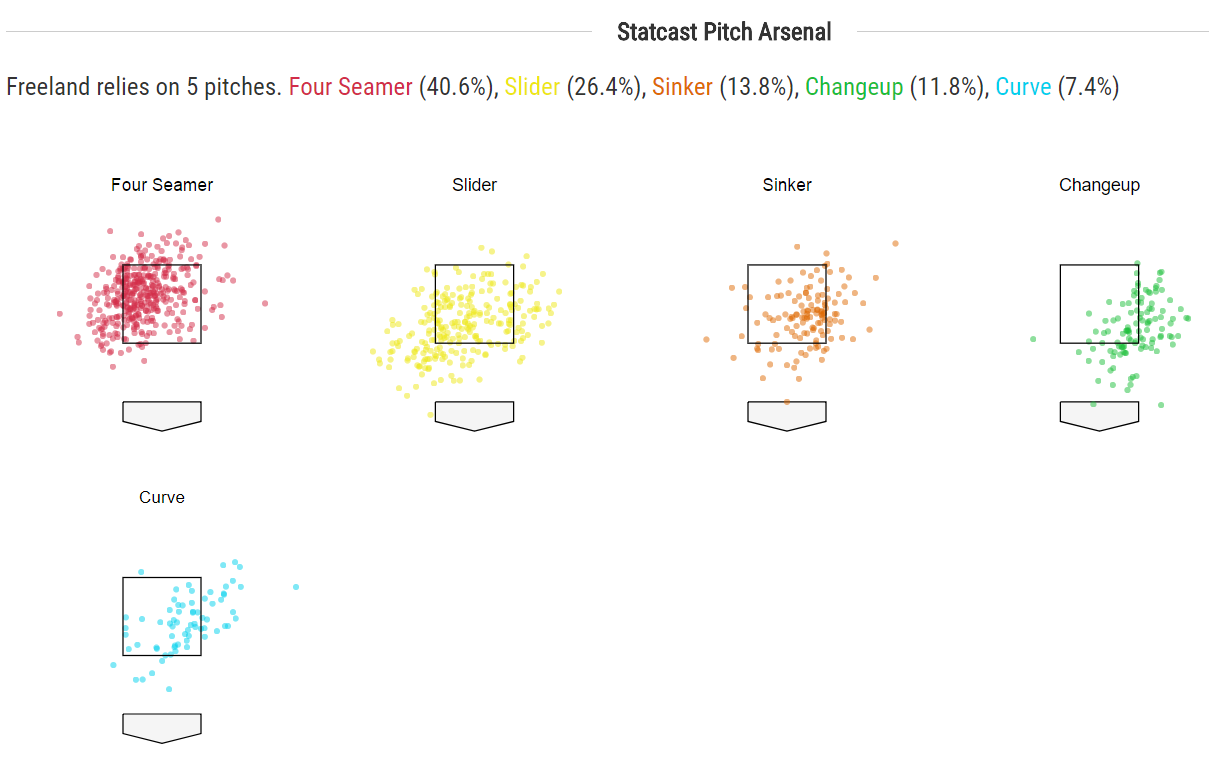

It is worth noting, however, that Brooks Baseball does not recognize Freeland’s curveball as such, but Statcast does, dropping his cutter from their measurements:

He throws his fastball slightly faster than most left-handers, sitting around 92.6 MPH. It does come in straighter than most, so he manipulates it to add drop and cut for his sinker and cutter at the expense of velocity to change hitters’ approaches to his hard pitches.

His changeup, coming in around 88 MPH, doesn’t have the velocity spread from the fastball as other pitchers, so he adapts his location and keeps it low.

His slider and curve use a sweeping action that misses bats, but as Brooks notes, does yield fly balls, especially when he misses location like the spray chart above indicates.

The Fastball

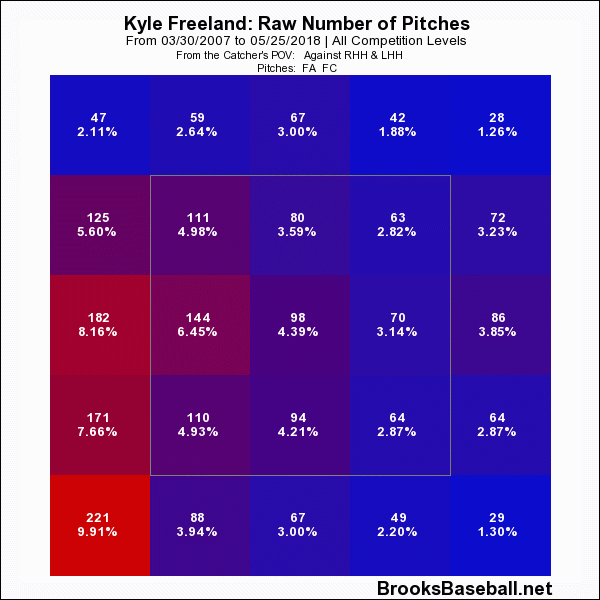

It should be no surprise that the pitch Freeland utilizes the most is his bread and butter. In this solid breakdown of Freeland’s arsenal by Fangraphs, it notes how a lot of his success is coming from the four-seam fastball in tight to righties and away from lefties. It also notes that while he does keep it low, he has elevated some over the most recent stretch of success to induce more swings. These swings, from both lefties and righties, result in ground balls over half the time they’re put in play, and a lot of that has to do with location.

He pounds the four-seamer in on righties to jam them and runs it away from lefties to complement the break on his slider.

This results in weak contact in on the hands for righties, making them pull the ball on the ground 44 times so far this season, tied for the third most in MLB.

That doesn’t hurt when you have Nolan Arenado and Trevor Story, who can then do things like this:

And this:

On lefties, he’ll only come inside with hard stuff using his sinker. Here’s his location on fastball variants without the sinker:

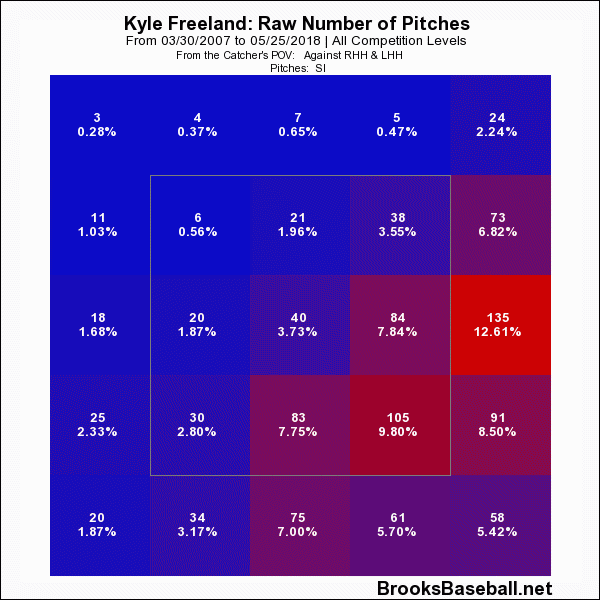

And here’s his lefty zone sinker usage:

What this does is let his less-effective fastball to lefties set up his offspeed pitches away, while still threatening the jam shot on them with a pitch that dives and can only be pounded into the dirt, like so:

So in summation, Freeland’s fastball serves to either jam hitters or set them up to chase his secondary pitches, allowing both types of pitches to induce grounders. Let’s look at his secondary now.

The slider

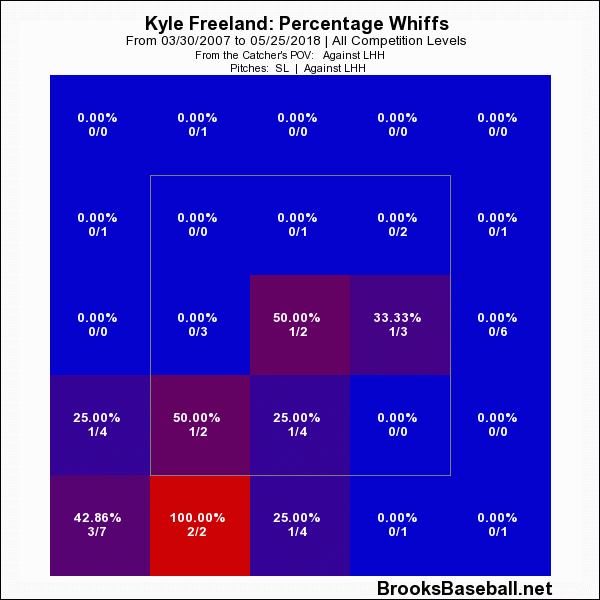

Conversely, Freeland runs the slider to the outside edge of the plate to both RHH and LHH, which is the intuitive use of the pitch and complements working the inside parts of the plate with fastballs well. This is especially effective to left-handers, who swing through the pitch often when he hits his spot:

This is showcased by the following Brandon Nimmo swing for the strikeout, who has been hitting at Mike Trout levels this season:

What really sets up the pitch is the preceding slider on the inside part of the plate on the previous pitch, listed as No. 4 in this zone chart:

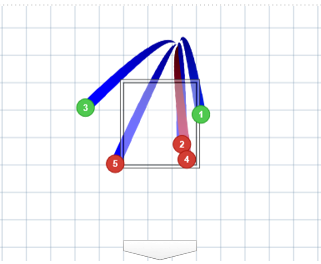

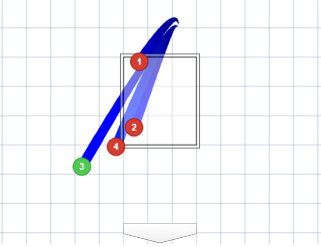

In that game, Freeland would strike out eight Mets, but the most defining one might be this one to Jay Bruce in the seventh:

What this chart shows is the true lethality of the pitch but also how it complements his curve. The first three pitches are sliders, the last is the curve. The only true difference between the two is the three MPH dip on the last one, which Bruce inevitably swings through.

It also helped that Freeland got whiffs on the first two pitches, and threw a very enticing slider on pitch three. When Freeland is effectively spotting on the outside edge like he did in this at-bat, he does not even need his fastball against left-handers.

The Changeup

Lastly, Freeland uses the changeup almost exclusively to right-handers, keeping it low and away to balance the fastball on the inside. Just like his other pitches, he uses it to get hitters out on their front foot, reducing contact quality because their frame is already outside of their base, and often getting the ball on the ground.

Here’s an example of that to Ben Zobrist, where the final result isn’t what Freeland or the Rockies were looking for, and frankly surprised all of us, but Freeland did his job and got the type of batted ball he was looking for off the change:

This ball does run over the plate, but four-hopping to Arenado gets you an out 95 times out of 100. If hitters jump out to meet the changeup, it should do this. At least, in theory.

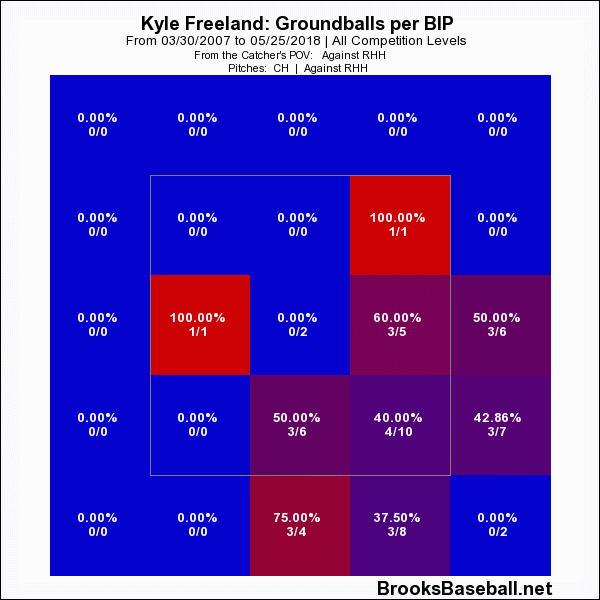

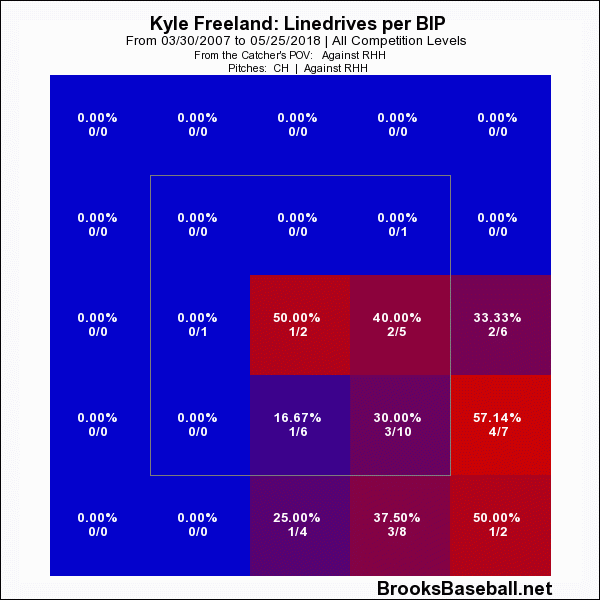

The change has been Freeland’s weakest pitch so far, with opposing hitters not swinging and missing or driving it into the ground. Instead, they’re hitting it hard. Here’s the line drive rate for that pitch against right-handers:

Ultimately, the change is a pitch that can be improved to miss more bats or create more ground balls. However, with the rest of his repertoire, the solution may be to just keep using it one out of every 10 pitches.

Summary

Like the true Denver native he is, Kyle Freeland knows that keeping the ball on the ground is essential to success in the spacious confines of Coors Field.

His ability to manipulate the inside part of the plate with hard stuff to both lefties and righties and follow it with soft pitches with solid break help him keep hitters on edge and off balance to produce weak contact. As of now, Freeland ranks 12th in MLB in groundball exit velocity and 11th in barrels per plate appearance, which pairs well with his high groundball rate to not only make his batted balls the least dangerous of any but also easier to handle for the excellent infielders behind him.

As long as Freeland continues to get hitters to chase inside and paint the edges with his slider and curve, it should surprise no one to see him representing Colorado in Washington D.C. on July 17.

Comments

Share your thoughts

Join the conversation