© 2026 ALLCITY Network Inc.

All rights reserved.

The lackluster Colorado Rockies offense nearly hit rock bottom on Tuesday.

A team that has struggled all season watched (in an almost literal sense) former Rockie Jordan Lyles carry a perfect game into the eighth inning. For those living under a rock and are hearing this news for the first time, don’t worry, we were all as shocked as you are.

Yes, that Jordan Lyles. The one that, by the time his tenure came to end, the Rockies trotted out whenever the game was too far out of reach, but someone needed to pitch the last nine outs. The one they didn’t trust to get important outs, or any outs, really.

But on Tuesday, against his former team, he was nearly flawless, further exacerbating the panic among the Rockies and their fans about an offense that has been underwhelming all season.

How did this happen, and was it a product of a bad offense hitting rock bottom or a castaway catching lightning in a bottle for two hours?

The pitch mix and attack

As with most things in life, the answer to that question is not black or white.

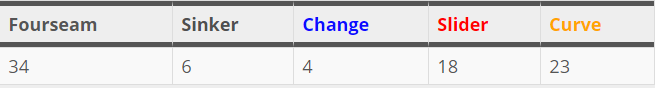

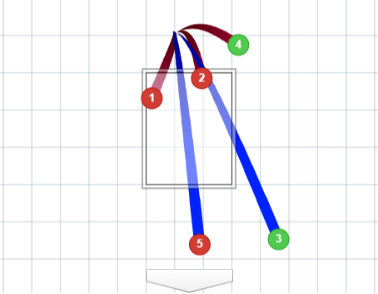

The Rockies are the only team in baseball who have more than 60 percent of the pitches thrown to them of the fastball variety. On Tuesday, Lyles threw fastballs at a 40 percent rate, or 47 if you include a sinker in that category. Here’s his pitch usage:

Of those 34 fastballs, 17 were on the first pitch, and 16 went for strikes. That means that after the first pitch, his fastball usage shriveled to once every three pitches, something unprecedented and ultimately unmanageable for the Rockies lineup. By getting ahead early, he was able to change up his arsenal and keep the Rockies off balance, but he had to get ahead first.

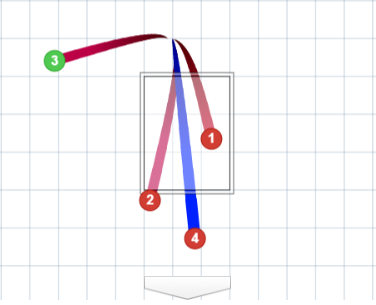

Lyles only went down 1-0 three times in the 24 batters he faced. He did not go down 2-0. Only six hitters watched ball two, and only Pat Valaika in the fifth got to a three-ball count before drawing a walk in the eighth. Simply put, Lyles got ahead and stayed ahead. In the first, he did it by painting the edges with the fastball. Here are the first pitches to the first three hitters of the game—David Dahl, Gerardo Parra and Nolan Arenado—respectively:

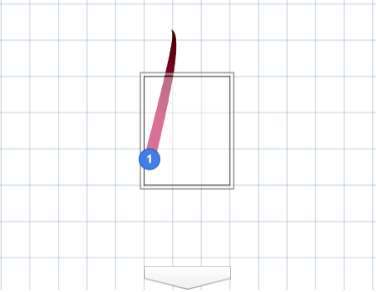

DAHL

PARRA

ARENADO

The initial pitch to Dahl catches a decent part of the plate, but it’s a fair bet that the first hitter of the game is passing on the first pitch. After that, the other two first pitches of the inning are on the money. Parra does exactly what Lyles was hoping for if he didn’t take, and the fastball to Arenado is pure execution, that Nolan is better off leaving and taking strike one and looking for something better to hit.

In this case, Lyles uses that to his advantage. It also then puts Arenado in the mindset that he needs to protect the outside edge because strikes will be called there.For Lyles, this sets up for sliders on the edge that he needs to attack, especially with two strikes. All the pitches he saw are away, and with two strikes he sees a pitch he thinks he needs to fight off before it dives away. Because he doesn’t get anything closer he doesn’t know better.

So, the first pitch strike in the first inning was a testament to Lyles’ location, and it set him up for success in the rest of the at-bats. Plus one Lyles. He would throw a couple middle-middle first pitches to Trevor Story and Valaika in the second, but would more or less live on the edges, especially with his first pitch, the majority of the game.

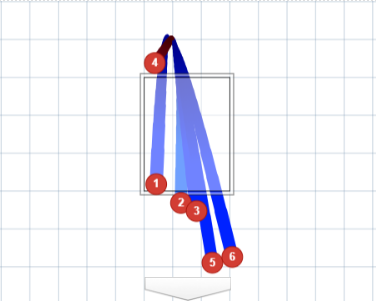

CARGO, FIFTH INNING

NOEL CUEVAS, SIXTH INNING

TONY WOLTERS, SIXTH INNING

DAHL, SEVENTH INNING

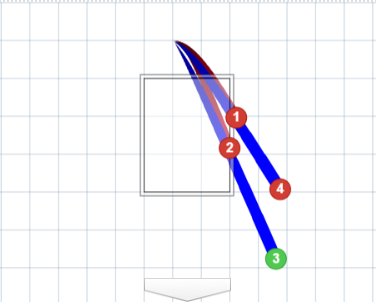

Lyles found the edges of the plate, only throwing a few pitches down the middle in the game as a whole, but only two real missteps down the pipe on first pitch early, preventing the Rockies from being able to jump on the first pitch while still getting ahead in the count. Here’s Lyles’ aggregate pitch location.

The curveball

Once he got ahead with the fastball, Lyles’ curveball carved up the Rockies the rest of the way. Of his 85 total pitches, 23 were the bender, which is good for 27 percent of his pitch usage. For the Rockies, who see the second-to-least amount of curves at 7.8 percent, the tripling in tendency was too much to handle.

Not only that, but Lyles got the Rockies to swing at 16 of those curves and miss eight. That swing percentage of 69.6 percent is nearly 20 points higher than baseball’s leader in the stat, Zach Davies, who only induces swings on the curve at a 52 percent clip. Quite simply, the Rockies weren’t prepared to see that many curves, but didn’t adapt either. It started at the top with Dahl, who struck out on the curve in the dirt twice.

In fact, the curve would be the knockout on six of Lyles’ career-high-tying 10 strikeouts. Here’s the other victimizations:

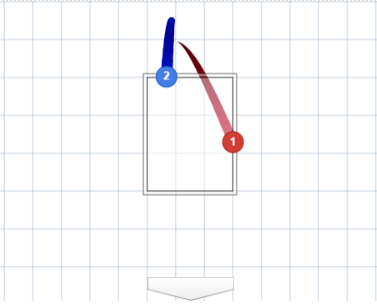

STORY, SECOND INNING

GERMAN MARQUEZ, THIRD INNING

CARLOS GONZALEZ, FIFTH INNING

CARLOS GONZALEZ, EIGHTH INNING

What stands out is that for as consistent as Lyles hit the zone and converted first-pitch strikes, all six of his punchouts via the curve were out of the zone on swings. To make a gross number worse, all 10 strikeouts were swinging, and not one was on a pitch in the strike zone.

As good as Lyles was early in the count, the Rockies helped him along the way, whiffing on 16 of his 85 total pitches. The team, who sees more fastballs than anybody else, could not adapt to the repertoire that they once watched give up run after run in their colors.

So, as much as you tip your cap to Lyles, you also have to criticize the Rockies on this particular day for their performance.

Comments

Share your thoughts

Join the conversation