© 2026 ALLCITY Network Inc.

All rights reserved.

(Click Here for Full Size Image)

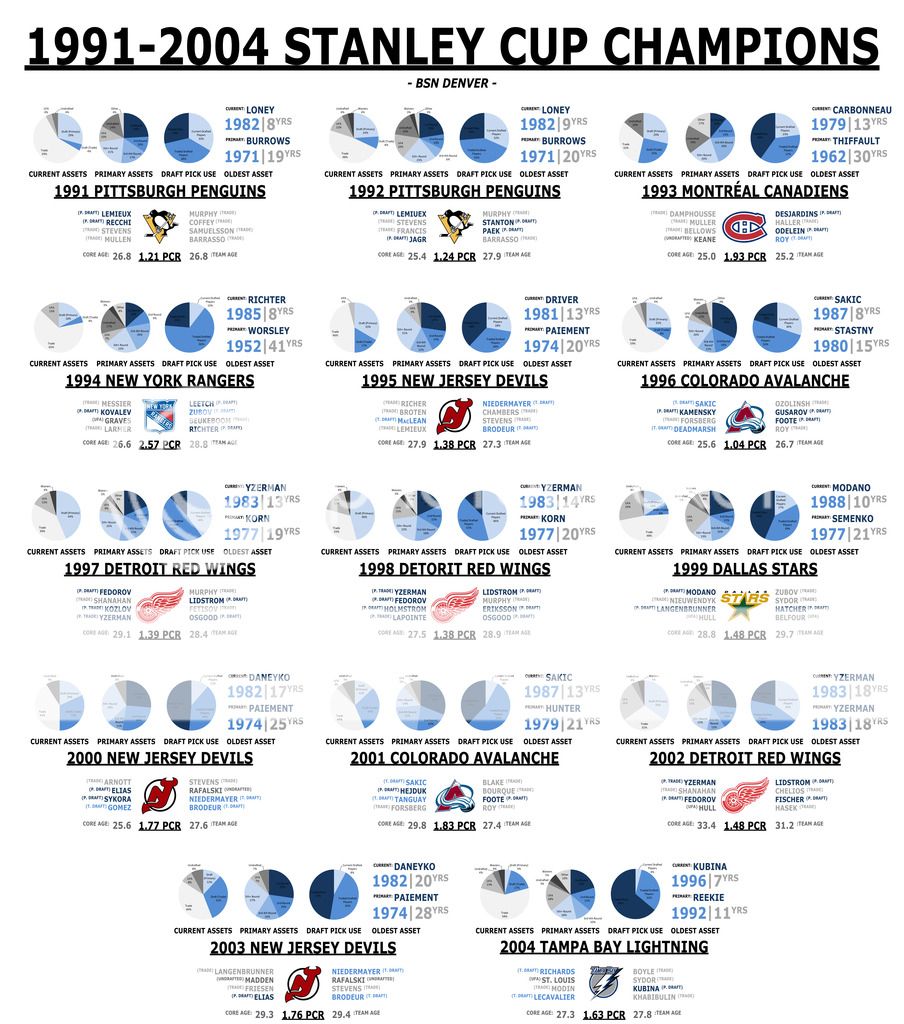

If the early 1990s set the groundwork for the 2005 lockout, it was the team building strategies of the late ’90s and early ’00s that cemented it. The high spending ways of the Rangers and Penguins were nothing in comparison to what the second half of the decade wrought.

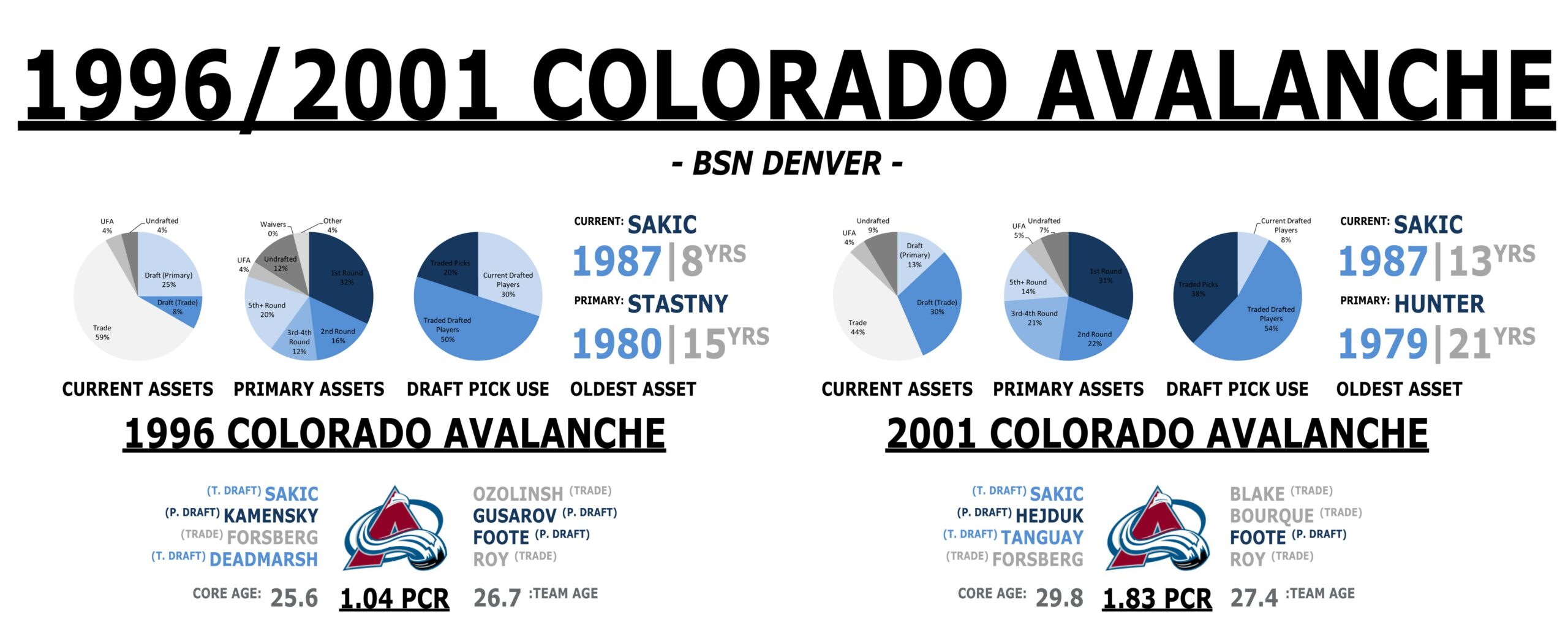

Although mired in the trap-crazed Dead Puck Era popularized by the New Jersey Devils, there were two teams in particular that rejected that approach. Instead, they opted to collect pure talent, driving salaries league-wide through the roof. Both organizations rose to be the powerhouses of the West, bitter rivals, and homes to some of the most impressive groupings of hockey talent in the history of the sport.

1996 Colorado Avalanche Data Sheet

2001 Colorado Avalanche Data Sheet

Hall of Famers: Sakic, Forsberg, Roy, Bourque, Blake

The first of these powerhouses needs very little introduction around these parts. However, for those not familiar with the Avs story (or for those that would like to re-live it), here’s a brief overview anyway.

The Quebec Nordiques spent a good number of years serving as the doormat for the NHL, occupying themselves with being near historically terrible and acquiring top five picks each year from 1988 to 1992. While only one of those picks (Curtis Leschyshyn) would lift the Cup with the Avs in 1996, it was a first overall pick by the name of Eric Lindros that would define it.

The hype around Eric Lindros in 1991 would have made even Sidney Crosby blush. By the time he was draft eligible, Lindros was 6′-4″ and destroying the OHL. As a result, he was dubbed to be the “Next One”, the successor to Gretzky and a player who would defined an era. With Joe Sakic already on the roster and a decent group of prospects working their way up the ranks, Lindros could have easily helped lift the struggling Nordiques out of the basement of the NHL.

Unfortunately, he wanted absolutely nothing to do with the team from Quebec.

Instead of jumping to the NHL, he opted to hold out for a full year by returning to the Oshawa Generals. The Nordiques, realizing that he wasn’t going to back down, orchestrated not one, but two deals to trade him at the 1992 Entry Draft. The first was with the New York Rangers, and the second was with the Philadelphia Flyers.

No one quite knew which deal would stand. The NHL decided to bring in an independent arbitrator by the name of Larry Bertuzzi, the cousin of a Bertuzzi who would become far less liked by Avs fans, who decided that Lindros belonged with the Flyers. In return, the Nordiques would receive the largest trade package in NHL history: six players, two draft picks, and $15 million in cash.

By the time 1996 arrived, the Lindros deal was at the core of nine roster players for the Avalanche, including Patrick Roy, Peter Forsberg, Adam Deadmarsh, and reigning Conn Smythe Winner, Claude Lemieux. By 2001, Alex Tanguay, Rob Blake, and Ray Bourque could also trace their roots back to Lindros. In total, the trade helped bring four Hall of Famers and two Stanley Cups to Denver. Both the ’96 and ’01 teams could trace well over a third of their roster back to this trade.

Beyond that drama, the Avs were very much a product of their era. Both of their Cup rosters were heavily trade-based affairs that used drafted players and picks as currency for immediate help. Very few of their original draft picks suited up for the team, and their GM was notorious for orchestrating massive multi-player trades.

With vast talent comes vast contracts, and the Avalanche were no different. In 1996, the young roster had a modest payroll of $20.6 million (11th in the NHL), but after a Sakic offer sheet from the Rangers in 1997, raises for Forsberg and Roy, and the addition of Rob Blake and Ray Bourque, the Avs’ expenses jumped to $50.5 million in just under five years. In 2001, 20% of the 25 highest paid players in the league wore the mountainous burgundy and blue.

This reckless building worked out very well for the Avs until the salary cap destroyed the team. Unlike Detroit, who was transitioning between cores at the time, the Avs core was still on the tail end of their prime. Jumping from a payroll of $60.9 million to $39.0 meant sacrificing critical players like Peter Forsberg and Adam Foote to the free market. Years of neglect, poor drafting, and trades had stripped the farm team of viable replacement options, so the Avs front office kept trying to use trades to construct competitive teams. Needless to say, it didn’t work, which lead the team to a full-scale rebuild in 2009.

The Avalanche’s system of building is probably the least compatible with the Salary Cap era. Although there are certain lessons that can be drawn from it, it’s almost impossible for any team (including the modern-day Avs) to duplicate it. It does, however, raise the question of what would have happened without the salary cap. Would the Avs have won more Cups? What would have happened to player salaries? Would the successful arms race of the Avs meant bankruptcy for other teams? All fascinating questions.

(Click Here for Full Size Image)

1997 Detroit Red Wings Data Sheet

1998 Detroit Red Wings Data Sheet

2002 Detroit Red Wings Data Sheet

Hall of Famers: Yzerman, Fedorov, Lidstrom, Fetisov, Murphy, Larionov, Hull, Robitaille, Chelios, Shanahan, Hasek,

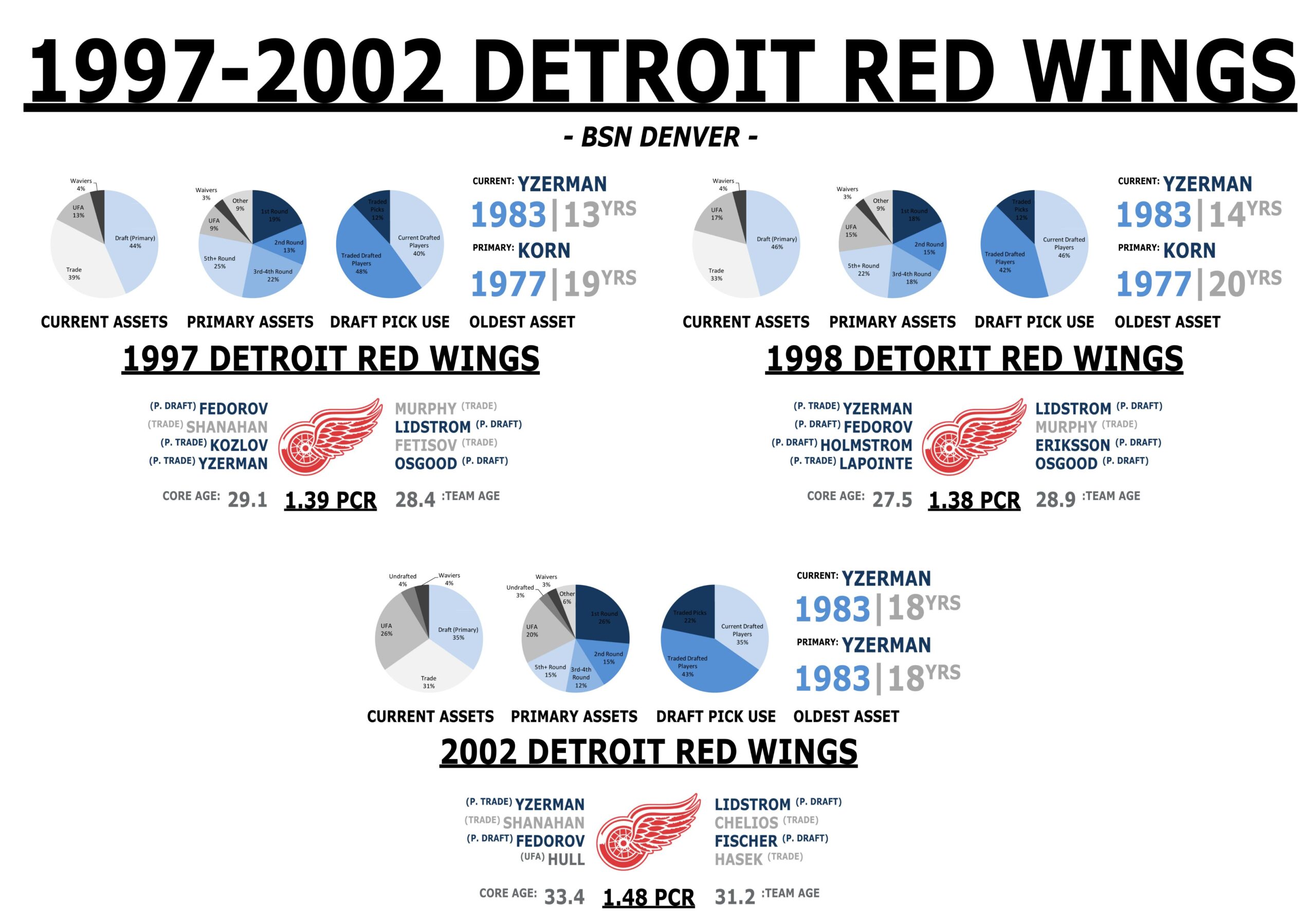

Meanwhile, another superpower was rising in the Great Lakes region.

In the course of this study, no team – not even the dynasty teams – have hosted a greater collection of future Hall of Famers than the late ’90s/early ’00s Red Wings. While not all of them played together, each wore the Winged Wheel within a 5 year period. A few were primary draft picks (Yzerman, Lidstrom, Fedorov), but most were brought in from outside the organization, including Fetisov, Shanahan, Murphy, Larionov, Chelios, and Hasek from trades and Hull and Robitaille from free agency. This doesn’t even include players like Pavel Datsyk (draft) who are likely to be inducted post-retirement.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the Wings dynasty is the fact that they didn’t incorporate traded draft picks. All three winning years, every player on their rosters were either original draft picks or acquired from outside of the organization. In stark contrast to the Devils, Avs, Stars and Lightning, they also didn’t trade many draft picks for immediate help, instead preferring the draft, develop, and then trade method.

Another interesting note is the prevalence of mid- and late-round picks that helped the Wings build. Nearly half of their primary assets in 1997 came from the third round and later. While that number dropped to around 25 percent in 2002, it speaks to both the drafting prowess and sheer luck that helped make these teams possible. Mid- and late-round picks are often a crapshoot, so to get Lidstrom, Osgood, Fedorov, Holmstrom, Datsyuk, and numerous other tradeable players from that region is a huge part why the Wings so successful for so many years.

World politics did had a hand in this success. The Soviet Union wouldn’t fall until 1991, but the Red Wings got a jump on courting Russian-born players far before most any other team. They drafted Sergei Fedorov and Vladimir Konstantinov in 1989, followed by Vyacheslav Kozlov in 1990. After adding Soviet veterans Fetisov and Larionov via trades in 1995, the team established a group known as the Russian Five, a strategy modeled after the five-man units of the Red Army.

The Wings oversees scouting didn’t stop with Russians. After a trip to Vasteras, Sweden in 1989, the Wings decided to use their third round pick on a smart, skinny defenseman with good puck control that none of the other teams had even heard of. Even though there was a chance he may never cross the Atlantic, it’s fair to say that Nicklas Lidstrom turned out to be an acceptable find.

1998 saw the addition of 6th round pick named Pavel Datsyuk, 1999’s 7th rounder became Henrik Zetterberg. As a result, this trend of taking chances on lesser known foreign players helped set up both the 1997-98 and 2008 Stanley Cup cores.

2002 is a slightly different case. Yzerman, the heart of that era’s core, was 36. Fedorov was 32, and Lidstrom was 31. Although history tells us that these players’ primes stretched far longer than average, at the time, it appeared that they were on the backside of their careers. The Wings went all in to try to win another championship, adding Hasek, Hull, and Robitaille the summer of 2001.

Unlike the ’97-98 teams and their reasonable $28 million payroll, the 2002 team cost $64.4 million to ice, which would have been above the salary cap even a decade later. By the 2005 lockout, Detroit was responsible for $77.8 million in salaries, making them the most expensive team in the history of the league.

Detroit’s success carried on through the cap era, including another Stanley Cup in 2008, but it’s finally beginning to wane. While they might be a playoff team, they aren’t the dominant force they once were. Better overseas scouting by all NHL teams has taken away one of their greatest edges, and the aging of the Datsyuk/Zetterberg core is beginning to show.

However, that doesn’t mean that principles they explored still don’t apply. While the sun might finally be setting in Detroit, their legacy is having a profound influence on a different organization, but that happens to be a story for another day.

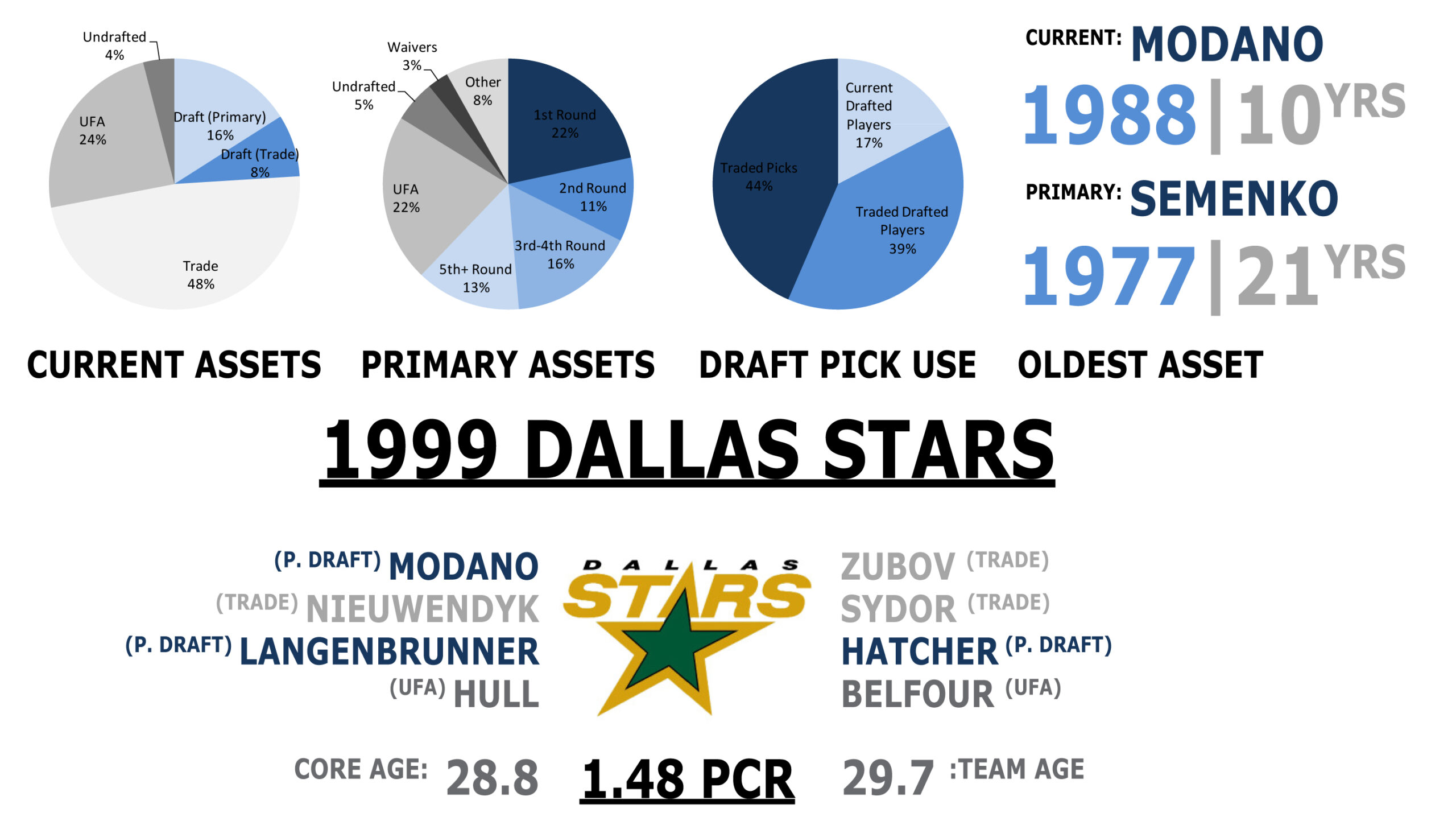

1999 Dallas Stars Data Sheet

Hall of Famers: Modano, Nieuwendyk, Hull, Belfour

Instead, let’s talk about the final Western power, the Dallas Stars. Even though they weren’t as dominant as the Avs or Wings during this period, they still did quite well in the arms race of the late ’90s thanks in part to their ample use of the UFA system.

Much like the Avs, the Stars were primarily built on trades and using draft picks as currency, but nearly 25 percent of both their roster and core were experienced veterans signed from outside of the organization. UFA Brett Hull was responsible for the infamous Cup Winning goal, and future HHoFer and free agency product Ed Belfour backstopped them in net.

Up to this point, no other team had built a winner so reliant on the free market. Detroit and the Rangers had made use of it, but there’s no doubt that Dallas took it a step further. It’s a strategy that would find success again three years later with the aging 2002 Red Wings, but unlike that team, the drafted core in Texas was still relatively young. Modano was only 28 when he lifted the Cup, and Langenbrunner was 23. Trade products Zubov and Sydor were still in their late 20s, and even Nieuwendyk wasn’t ancient at 32 years of age. It was certainly a mature roster, as many during this trade-fuel time were, but the UFA assets helped push an already strong in-their-prime core over the edge instead of simply extending its life.

This new concept separated Dallas from the other teams of the era, but the cost of such a strategy was daunting. In 1999, the Stars had the second highest payroll in the league, clocking in at $39.9 million. Modano and Hull were both within the 25 of player compensation for that season, and Belfour and Verbeek both broke the $3 million mark. This payroll was more than 4.5 times that of the high rolling Los Angeles Kings a decade before, triple that of the 1999 Nashville Predators, and double what the Dallas club had paid only three years ago. Despite all this, they still trailed behind the 1999 Red Wings’ commitments by over $8 million that season, demonstrating just how wide the gaps between teams were becoming.

Even so, the concept of a UFA-heavy core would transfer surprisingly well into the upcoming cap era. Despite its obvious pitfalls (with obscene cap hits often leading the way), the shift from the pre-lockout trade culture to a more mixed post-lockout one paved the way for more teams built using the method. It’s easy to argue that the 1999 Dallas Stars are at least partially responsible for this trend.

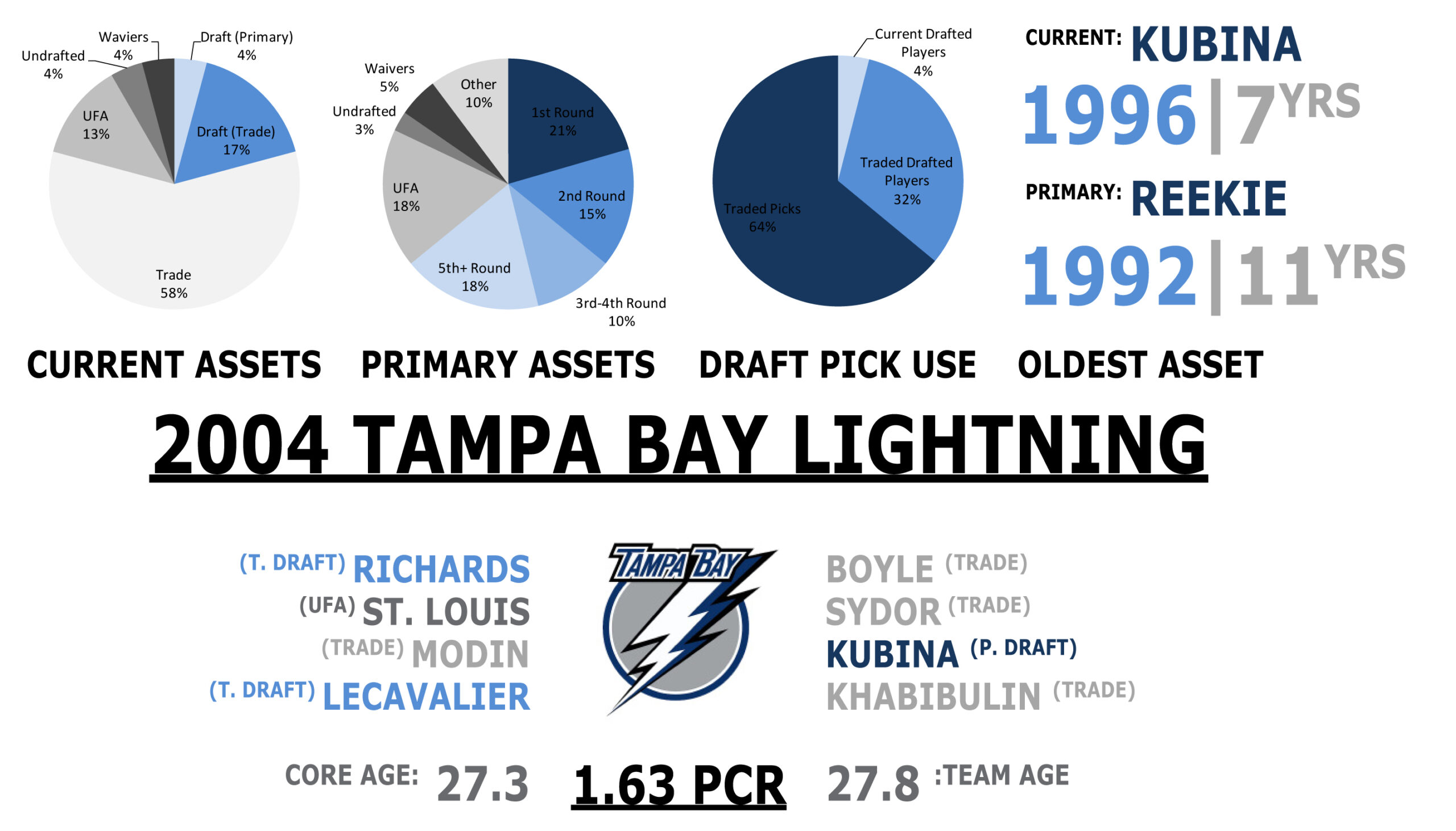

2004 Tampa Bay Lightning Data Sheet

In comparison to the rest of the teams mentioned today, the 2004 Tampa Bay Lightning were downright cheap. Coming in at $33.5 million, they actually sat below the league average of $44 mil and the payrolls of 18 other teams. Three clubs – Dallas, NY Rangers, and Detroit – spent more than double this allowance on their rosters, and Tampa only allocated $10 million more than the lowest spending team to bring home their Stanley Cup.

The fact that most of their stars were still fairly young certainly helped. Brad Richards and Vincent Lecavalier, both products of the 1998 draft, were only 23 at the time. Martin St. Louis was 28, but he joined the league as an undrafted player the same year as his younger teammates. This lack of experience helped keep their prices under control and within the reach of a team only in its 11th season of existence.

Beyond them, Tampa’s roster was a collection of players primarily acquired via trade that didn’t particularly stand out, but proved to be an effective unit on the ice. 2004 marked only the third trip to the playoffs for the Floridian team, as well as their first trip past the second round. Under the leadership of John Tortorella, they beat Calgary for the ultimate hockey prize in a Game 7 on home ice.

So, how did they get here? Mostly, they mortgaged their future. From 2000 to 2004, they traded away 14 picks or young prospects, including a 3rd, 4th, and 5th Overall selection. All but their 2004 second round pick were shown the door as well. Although their strategy clearly accomplished their goal of winning the Cup, it’s little surprise that the franchise earned a 1st Overall selection only four years later.

While the Lightning served as a break from the high price of success that dominated the era, the damage had already been done. After the lights went down in the St. Pete’s Times Forum, they sprang up in boardrooms. Teams like the Penguins, Senators, and Sabres had all filed for bankruptcy within the past 7 years, and the Oilers, Capitals, and others probably weren’t far behind. Small market and expansion teams were having a hard time even paying the bills, let alone being competitive against clubs spending two or three times what they could afford. Add in an aggressive Commissioner and bad blood from the last lockout, and the feud would cancel a season.

Blame who you will for the lockout, the egos and greed, and the needless wasting of a full hockey year. However, after the arms race of the ’90s, the rich kept getting richer and the poor kept getting poorer. The salary cap, for all of its flaws, has probably saved numerous NHL teams. It deterred reckless spending (or at least made it much more creative) and has fundamentally changed the ways teams were forced to operate and build.

Comments

Share your thoughts

Join the conversation