© 2026 ALLCITY Network Inc.

All rights reserved.

(Click Here for Full Size Image)

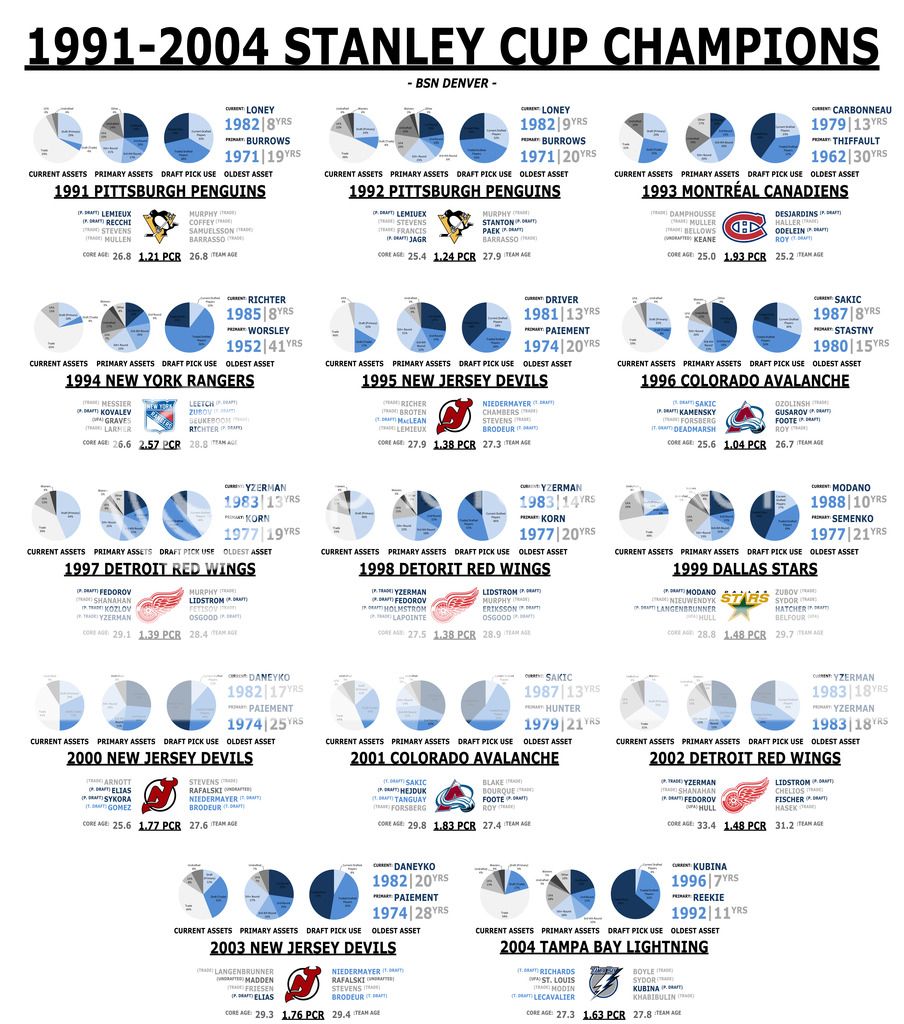

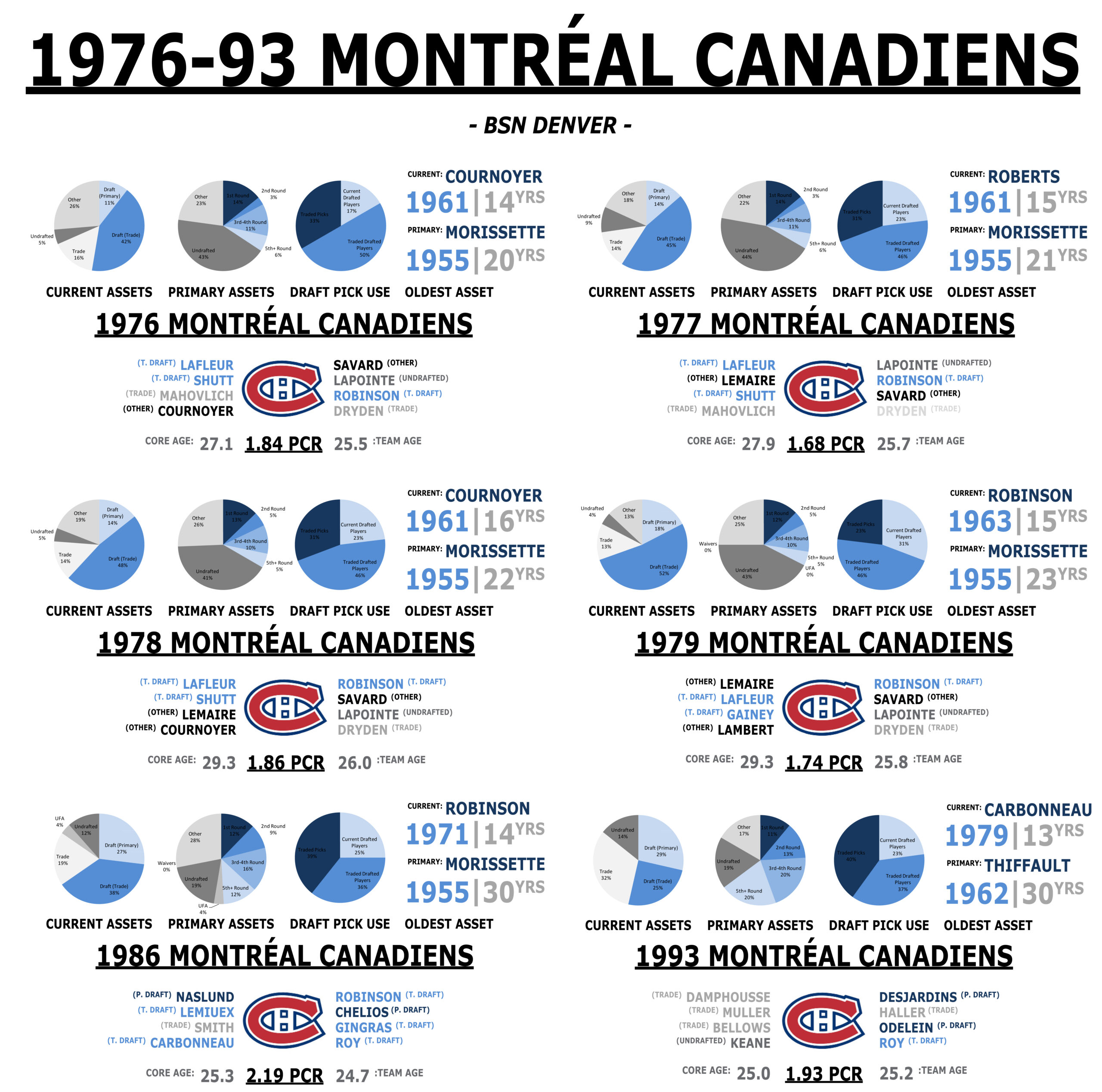

As we saw yesterday, teams during the dynasty era primarily built their clubs through the draft and other young players. Each of the three main organizations went about this task in a slightly different way – Montreal through acquiring picks in trades, the Islanders by using their own, and Edmonton through a series of claims and good first and second round choices – but they all acquired their players young and managed to retain them for a number of years.

That all started to change by the time the 1990s rolled around. Winning in the NHL was no longer about having the best drafted players – it became about acquiring top talent via trades. More talent meant more payroll, which owners raced to spend.

Fueled by rising revenues and expansion fees as the NHL aggressively spread into new markets, the average payroll for an NHL team rose nearly 700% in the decade and a half before the lockout. Some of the main drivers behind this rise? The Penguins, Rangers, Red Wings, Avalanche, and Stars – all teams that won Stanley Cups during this era.

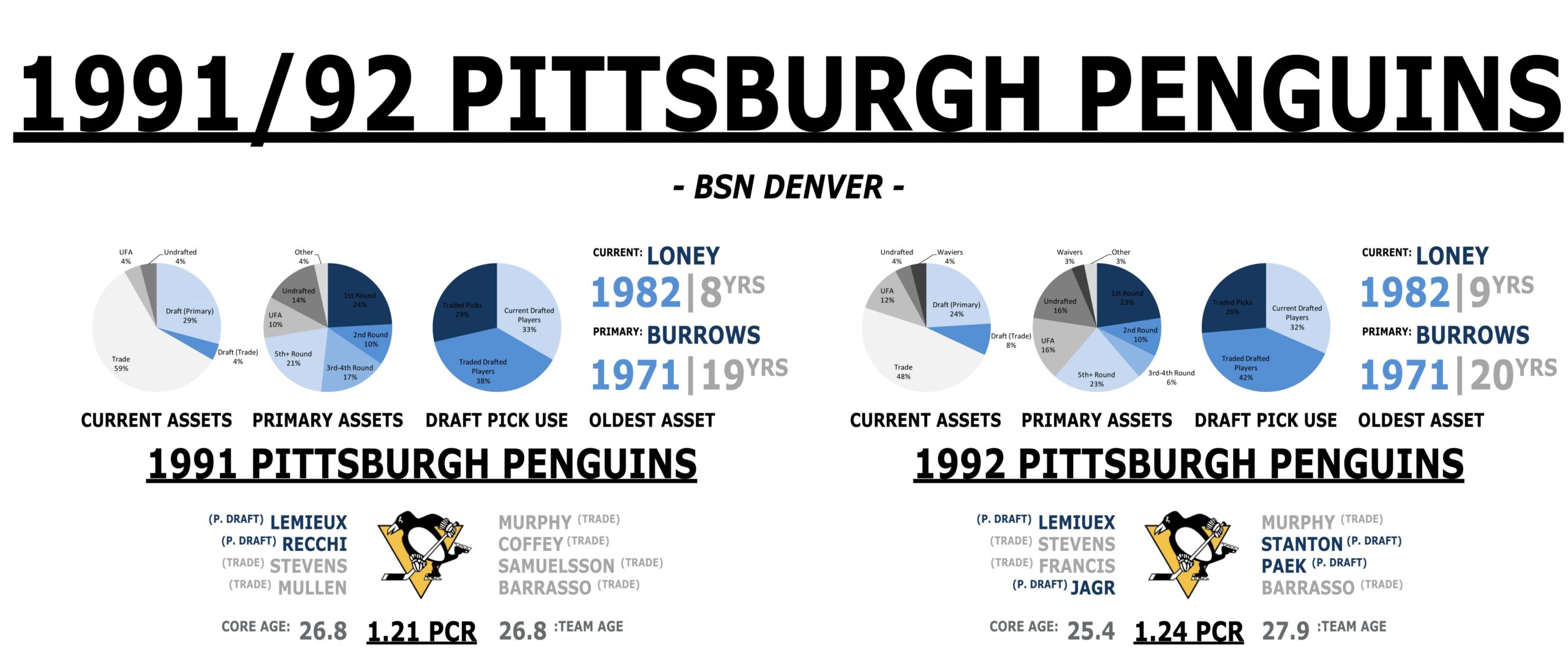

1991 Pittsburgh Penguins Data Sheet

1992 Pittsburgh Penguins Data Sheet

Hall of Famers: Lemieux, Coffey, Francis, Mullen, Murphy, Trottier, Jagr (likely)

The 1991 Penguins are the first really trade-based team of this study. Even though the ’89 Flames and ’90s Oilers used trades to help build their team, they didn’t rely on them to the extent of the Penguins. While drafted players Mario Lemeiux, Mark Recchi, and Jaromir Jagr were all major cogs for the team during this time, Hall of Famers Coffey, Francis, Mullen, and Murphy were all brought in via trades. Brian Trottier also joined the team through free agency.

As one can imagine, this array of future Hall of Famers acquired from outside the organization didn’t come cheap. In 1991, the Penguin’s team salary was $9.8 million, seventh in the league and trailing the top spending Whalers by only $1.4 mil. Only a year later, raises kicked in and the Penguins jumped to first overall to the tune of $14.5 million.

While these amounts seems minuscule today, keep in mind that the salary floor – the minimum amount NHL teams must spend – is currently around 74 percent of the salary cap. In 1992, the brand new San Jose Sharks had a payroll of only $6.2 million, 43 percent of the Penguin’s salaries. Assuming the Penguins payroll to be the cap, to be modern day complaint, the Sharks would have needed to add $4.5 million dollars – an additional 73 percent of their payroll – just to get over the floor.

To complicate matters, April 1992 marked the beginning of this period’s hallmark labor unrest. For ten days, the players held a strike that delayed the hockey season. Many of the issues stemmed from a dispute over playoff bonuses, a better split of hockey card revenue, and changes to the free agency and arbitration systems. While this didn’t have a direct affect on how much the players were during the regular season, it did show how serious they were about getting their share of the league’s revenue. This set the table for the larger fights down the road.

(Click Here for Full Size Image)

1993 Montreal Canadiens Data Sheet

Hall of Famers: Savard, Roy

More than anything, the 1993 victory by les Habitants was a holdover from the bygone dynasty era. Even though only two players were a part of both the ’86 and ’93 wins (Carbonneau and Roy), many of the same team building strategies where utilized.

Despite the fact that the roster was mostly draft-based, the core interestingly was not. Vincent Damphousse, Mark Muller, and Brian Bellows – all products of trades – lead the team in scoring during the playoffs, and Keven Haller helped from the blueline. Unlike in previous Habs Cups where one, maybe two players were brought in from trades, these acquired players represented half of the nucleus of the ’93 iteration. This trend showed an interesting blend of traditional Habs sensibilities and the increasingly trade-based culture surrounding the NHL.

Even though the team had added a few pricier trade assets, the Canadiens were only a middle of the road team salary-wise. Their $10.3 million payroll placed them at 10th Overall and barely above the league average in 1993. The fact that the were (and would remain) one of the most draft-based teams of the era probably contributed to their middle-means success. As a result, this strategy would become heavily revisited in the post-Lockout era.

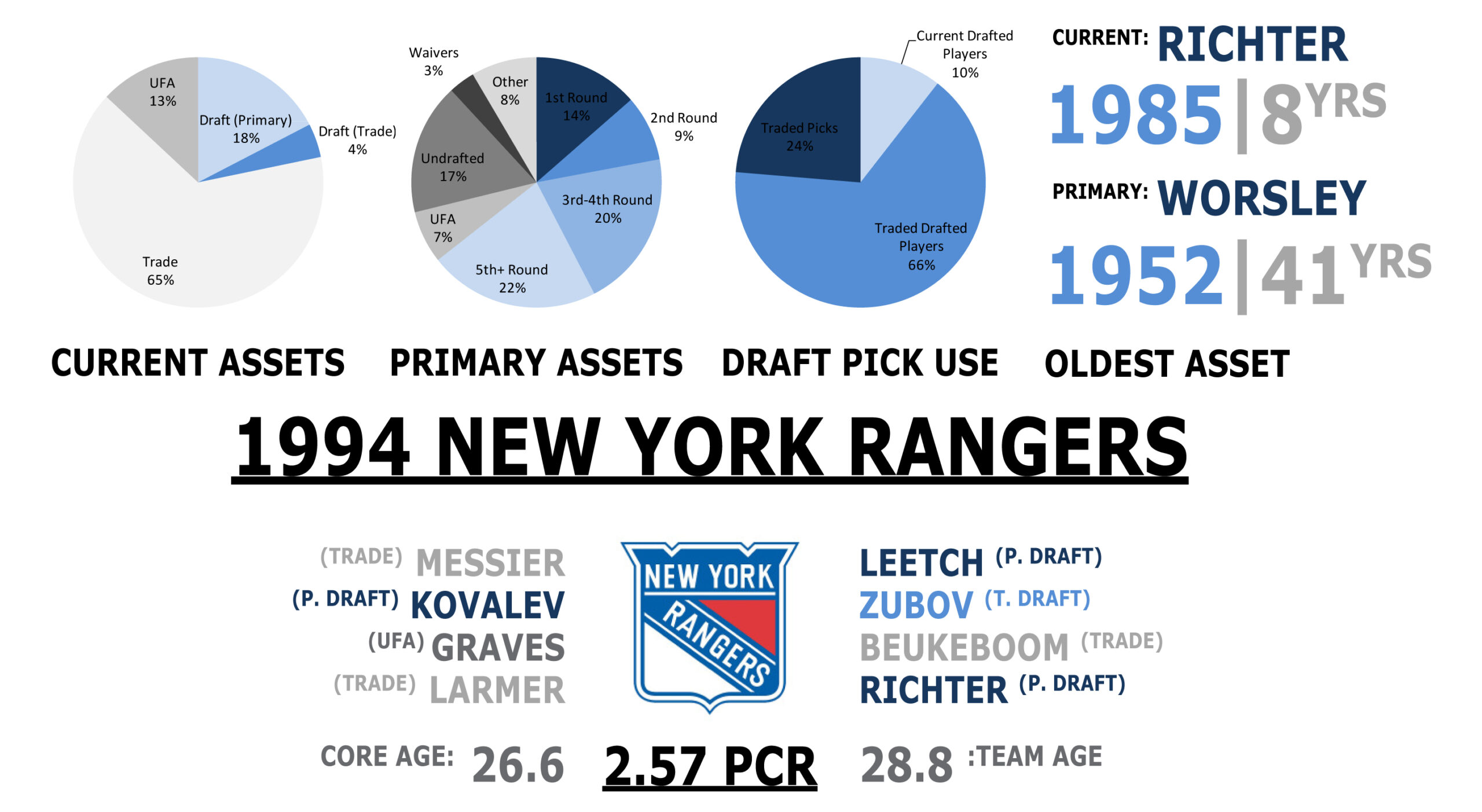

1994 New York Rangers Data Sheet

Hall of Famers: Messier, Anderson

Unlike the draft-based Canadiens the year before, the 1994 Rangers were almost entirely built through trades. 18 of the 23 Blueshirts began their careers with a different team, and 15 of those were acquired directly via a swap. However, three of their top four scorers (Brian Leetch, Alex Kovalev, and Sergei Zubov) were drafted, representing well over half of the five total New York Rangers draft picks present on the roster.

Where did all the other draft picks go? Even though the current composition of the roster would lead one to believe that the Rangers were bad at drafting, that wasn’t the case. Starting in 1966, the Rangers drafted 25 players that appeared in their 1994 trade trees. This doesn’t even count the nine draft picks they moved as well – all in all, they salvaged on average 1.25 tradeable assets from each draft over that 27 year period. For a trade-based team, that is an impressive amount of ammo!

Building Rangers teams through trade wasn’t something new. The ’94 iteration could still trace its roots back to three Original Six era C-Form players, including HHoFer Gump Worsley, a goaltender who first suited up for the team in 1952. Those assets were used to obtain future Hall of Famer Mark Messier, who would captain the team to their first victory in 54 years. Various other long trees dotted the roster, especially the ones for Eddie Olczyk and Glenn Anderson.

The Rangers paid handsomely for their winning strategy. Slotting in at 2nd behind the Pittsburgh Penguins in payroll during the 1993-94 season, the team ponied up 19.4 million for the Stanley Cup. $2.385 million of that belonged to Messier, making him the 6th highest paid player in the league. Brian Leetch also broke the top 25 with his $1.8 million, and 4 other Rangers breached the $1 million mark.

In comparison, the lowly Ottawa Senators managed to spend only $7.7 million, just over a third of the Penguin’s $20.7 million payroll. Player salaries were going up at an unprecedented rate, and the small market and expansion teams were struggling to keep up.

It’s also probably important to mention that 1993-94 was the first full season played under Gary Bettman as NHL Commissioner. I have a feeling that little fact is about to become very relevant in three… two… one…

(Click Here for Full Size Image)

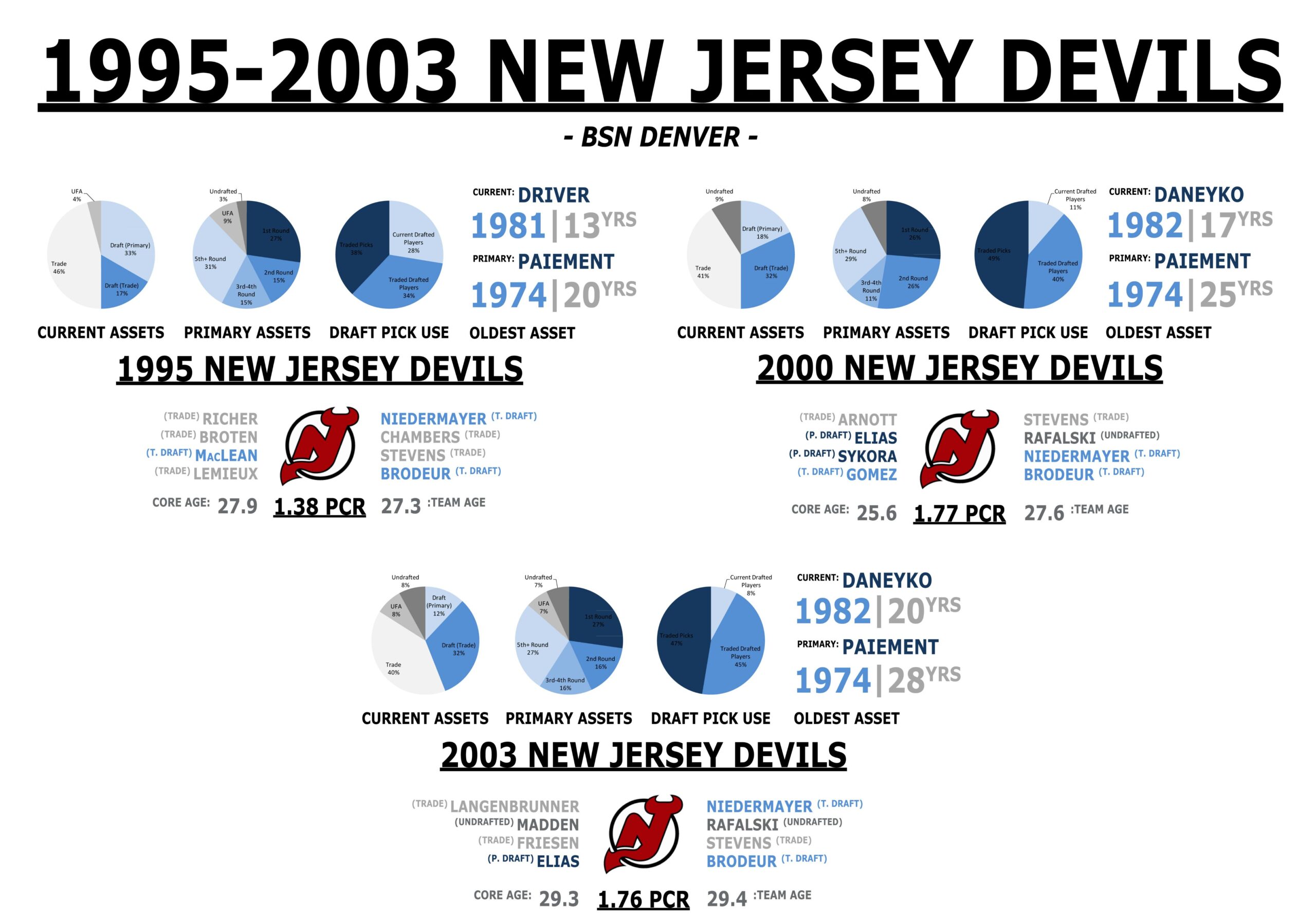

1995 New Jersey Devils Data Sheet

2000 New Jersey Devils Data Sheet

2003 New Jersey Devils Data Sheet

Hall of Famers: Stevens, Niedermayer, Nieuwendyk, Brodeur (likely)

Hey look! An NHL Lockout! We’ve not had one of those yet!

Thanks partially to the Rangers dramatic victory and overall growing interest in the sport, there was talk of the NHL challenging the NBA for the title of third most popular sport in North America. However, the ballooning player salaries – driven mostly by large markets trading for and paying high-end talent – had skyrocketed operating costs league-wide. Many of the smaller markets and expansion teams were struggling to compete.

So, naturally, the NHL owners met this challenge by canceling half the season.

Certain concessions were met, such as a cap on rookie salaries and some changes to arbitration, but no salary cap or cap on player salaries were established. This did nothing to deter the high spending, trade-based arms race that had been brewing for the past five years. All it did was poison the water between the NHL and the Players Association, set up a knock-down drag-out lockout ten years later, and kill virtually all of the popularity momentum the league had gained heading into the dispute.

To return that momentum, the league really could have used an exciting, high scoring, big-market team to win the 1995 Stanley Cup and woo back disgruntled potential fans. Instead, they got the New Jersey Devils.

Now, that’s not to say the Devils weren’t a good team. They were very good… three Cups in eight years good, to be exact. However, their infamous defensive system popularized the neutral zone trap, which lead to decreased league-wide scoring and a time eloquently known as the Dead Puck era.

Even though their teams were split nearly 50-50 between drafted and non-drafted players, trade products made up a large percentage of their cores, especially in 1995. Two of their Hall of Famers, Scott Stevens and Joe Nieuwendyk, were direct products of trades, and Scott Niedermayer and Martin Brodeur were both from traded draft picks. A few more primary assets joined as the years went on (such as Elias and Rafalski) but New Jersey retained fewer and fewer of its original picks.

However, they did keep using traded picks, which correlated to lower salaries over the course of their mini-dynasty. In their 1995 and 2003 wins, the Devils paid around 75 percent of what the highest roller did, and in 2000, they came in at 53 percent.

They may not have been the most exciting team, but there’s no doubt they were effective. In fact, during this time period, they were the only Eastern team to withstand the growing powerhouses in the West. These giants – including one very familiar to fans in Denver – will be discussed at length tomorrow.

Comments

Share your thoughts

Join the conversation